Assessing adaptation knowledge in Europe: vulnerability to climate change

Introduction

This project* is a knowledge assessment study designed to synthesise the frameworks, processes and methods being used to assess vulnerability in Europe. It describes the concepts and definitions covering impacts, vulnerability, risk, resilience, adaptive capacity.

A selection of European research projects focusing on national and transnational level assessments were reviewed. The current status of European Member States’ risk and vulnerability assessments were analysed initially through the country information pages on Climate-ADAPT. The study then synthesised the information from EU research projects and EU Member States to provide a reference framework that can be shared with those who are considering developing risk and vulnerability assessments. Finally lessons learned, gaps, challenges and recommendations are provided.

The primary focus for the task is on vulnerability assessment methods (and related concepts of impact, risk and adaptive capacity) that have been undertaken at the national level (characterised by a method applied to multiple sectors). Individual sector or, city level assessments are not part of this study.

*Download the full report from the right-hand column.

Methods and Tools

A selection of European research projects focusing on methodologies for national and transnational level assessments were reviewed based on inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- The frameworks and methodologies used in the EU research projects were analysed and summarised as lessons learned, gaps and challenges (section 2, p.13).

We have used the criteria to select 8 research projects (Baltic, BASE, CLIMSAVE, ESPON, MATRIX, MEDIATION, PESETA I and II and RAMSES) that were the most relevant based on the criteria, and availability of resources and time to conduct the analysis.

- As such, the analysis undertaken highlights some of the EU research on vulnerability assessment (frameworks and methodologies), but also provides further information on the methodologies used in some countries’ national assessments.

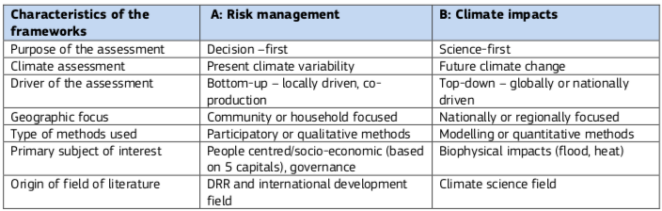

The results show that the frameworks used in the research projects fit within the continuum between climate impacts and risk management.

- Analysis of the characteristics within the different frameworks provide a range of characteristics such as geographic focus from national to household, which field of literature it originates from e.g. DRR or adaptation and whether it assesses present climate variability or future climate change.

- The characteristics at either end of the continuum are provided in table 2 (reproduced below). Most projects and national assessments cover features within both perspectives and are positioned somewhere between the two ends.

- This probably reflects the shift in framing and sharing of concepts over the past 20 years, and the influence of the IPCC assessment reports and guidance.

- It also reflects the purpose of the project in that some projects are aiming to have a European overview of e.g. economic impacts with no expectation that this will be used for national policy planning.

- Whereas, some assessments are locally specific and designed to a feed into development of adaptation options for e.g. a city hence, it would be expected that the methods and framings for these two different purposes would be different.

Key findings

There has been a significant increase in the knowledge base for national vulnerability assessments since 2014, with 21 out of 28 EU countries having completed a vulnerability assessment.

- However, the assessments vary significantly in their level of detail.

- The knowledge base has also been boosted by a number of EU-funded research projects such as, ESPON and PESETA.

- This has helped countries with no national level assessment to prioritise their risks supported by a stronger evidence base.

A number of countries are either in the process of, or have completed a second assessment.

- Typically the first assessment focuses on biophysical factors.

- Subsequent assessments aim to fill any gaps, for example, incorporating data on social factors, greater coverage of sectors or impacts, involving more stakeholders, further research and the creation of data at smaller scales/finer resolution e.g. city level.

When measuring vulnerability using indicators, countries have used blended or ‘mixed-methods’.

- This involves multiple sources of information and combining quantitative and qualitative methods:

- e.g. using a range of indicators (process, output and outcome), alongside stakeholder perspectives gained through self- assessments or surveys and consultations with experts.

The countries have used a number of different techniques to account for uncertainty such as:

- Estimating uncertainty within the climate projections: using multiple runs of climate models, using multiple storylines or scenarios for emissions and socio-economic projections and considering the outputs from many GCMs/RCMs models.

- Indicating the robustness of the evidence by: calculating confidence levels from low to high, use of probabilistic (10th/90th percentiles), or ranges (min/max) in data outputs and use of uncertainty methods, for example, sensitivity analysis, fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making.

- Exchanging knowledge with stakeholders: both gathering evidence to address uncertainties and communicating the uncertainty e.g. visualisations, to those that need to use it.

- However, most assessments would benefit from more comprehensively addressing uncertainty. Providing guidance on how to address uncertainty would be one way of supporting improvements in vulnerability assessments.

Most countries have used the IPCC definitions (AR4, AR5) of vulnerability and related concepts highlighting the influence of a trusted, international source of knowledge and the benefits of a common understanding of terms.

- This is particularly important when different arenas – economic, DRR, climate science communities– use the same terms but with different meanings.

- The team involved in a vulnerability assessment should aim have an agreed understanding of the terms related to vulnerability at the start of the process.

Highly vulnerable groups that are actively engaged in the process generate broader insights which are more likely to guide decision-makers into developing policy (and supporting guidance) that will increase the equity and resilience of vulnerable groups.

- In addition, countries that have allowed time for consensus building have considered it to be well worth the effort as the decisions made from the evidence are more robust.

National vulnerability assessments of climate change benefit from using a consistent (i.e. the same climate projections), integrated methodology that allows comparison between, and across sectors and risks.

- National vulnerability assessments also benefit from using a wide range of methods to gather evidence from primary and proxy sources including quantitative e.g. modelling, and qualitative e.g. stakeholder opinions.

- The choice of methods and framework should remain flexible and determined by the purpose and resources available for the assessment in each country.

Recommendations

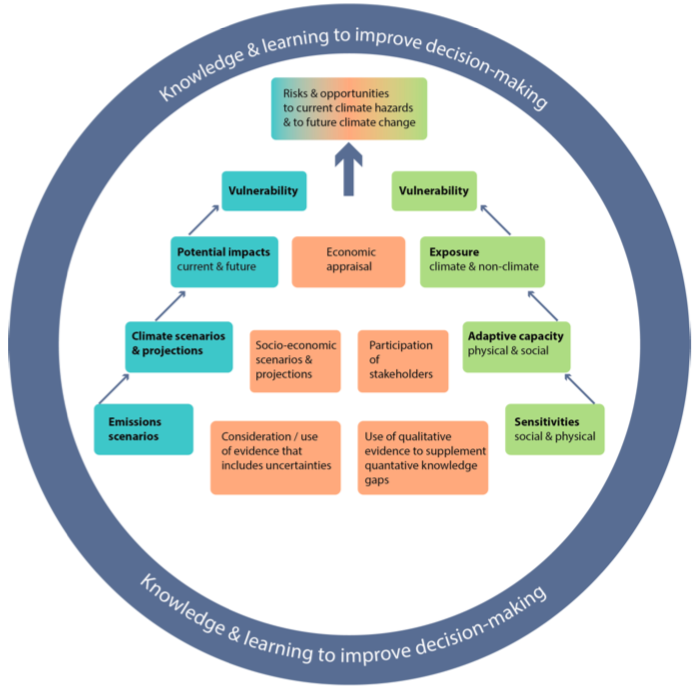

It is recommended that the following elements should form part of a vulnerability assessment (figure 8, see above):

- Emissions scenarios

- Climate scenarios and Projections variability and change

- Potential Impacts (current and future)

- Sensitivities physical and social

- Adaptive capacity physical and social

- Exposure climate and non-climate

- Vulnerability (social and biophysical)

- Socio-economic scenarios and projections

- Economic appraisal

- Uncertainties are acknowledged and addressed

- Use of qualitative evidence to supplement quantitative knowledge gaps

- Risks and opportunities

- Participation of Stakeholders

The purpose and the framing of an assessment, as well as the knowledge and science capacity available, will determine which methods are chosen for the assessment.

- It should be noted that a vulnerability assessment undertaken under one framing will give different results to an assessment undertaken with another.

- Understanding these differences (the strengths and limitations) will help identify an appropriate framing and methods for the intended purpose.

- This understanding is important, as the results of the vulnerability assessment will greatly affect the selection of adaptation options and ultimately the success, or failure of the policies to reduce vulnerability, or exploit opportunities to climate change.

Authors

By: Clare Downing (UKCIP). Contributions from: Roger Street, Patrick Pringle and Vicky Hayman (UKCIP), Coraline Bucquet, Kristen Brand and Sarah Hendel-Blackford (Ecofys).

Suggested citation

Ecofys, 2016. Assessing Adaptation Knowledge in Europe: Vulnerability to Climate Change. Available online here.

Further reading

- Issues around developing and working with vulnerability indicators at the urban level in Europe

- The Vulnerability Sourcebook: Concept and guidelines for standardised vulnerability assessments

- A Framework for Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments

- A closer look at the practices of vulnerability assessment and the priorities of adaptation funding

- Dynamic Interactive Vulnerability Assessment model

(0) Comments

There is no content