Artefacts of Disaster Risk Reduction: bridging the gap between policymaking and capacities on the ground

Introduction

In times of global warming, disaster risk reduction poses a great challenge for governments and organizations in the Global South. The challenge is even greater in informal settings: that is, in contexts where housing and economic activities emerge primarily from residents’ efforts. In slums, barrios, favelas, tugurios, comunas, and other low-income neighborhoods, residents must try to secure access to water, sanitation, shelter, and other services in parallel with, or without, government action. Two major obstacles to disaster risk reduction arise. First, climate policy designed by national governments rarely responds to the needs and expectations of citizens living or working in informal settings. Second, policy- and decision-makers tend to disregard people’s claims for social and environmental justice, and their bottom-up initiatives, perceptions, and ways of dealing with risk.

Artefacts of Disaster Risk Reductionexplores how to bridge the gap between inefficient top-down policymaking and the often-neglected capacities on the ground. The term “artefacts of disaster risk reduction” has been coined to refer to the set of rituals, practices, events, and spaces that make it possible for people in informal settings to work together, develop trust, and reduce or manage the multiple risks they face.

This online publication results from a four-year effort titled ADAPTO (Climate Change Adaptation in Informal Settings: Understanding and Reinforcing Bottom-Up Initiatives in Latin America and the Caribbean). In this action-research project, the implementation of 22 bottom-up initiatives has been studied over four years in four cities: Carahatas (Cuba), Yumbo (Colombia), Salgar (Colombia), and Concepción (Chile).

This weADAPT article is an abridged version of the original text, which can be accessed from the Artefacts of Disaster Risks Reduction website. Please access the original text for more detail, research purposes, full references, or to quote text. To learn more, explore the final technical report of the ADAPTO initiative, or download one of the policy briefs in the right-hand column, ©Dhar, et al. (2021).

Facing climate change in informal settings

Climate warming scenarios for Latin America and the Caribbean predict a mean temperature increase of roughly 4.5°C by the end of this century. Higher temperatures increase the frequency and severity of droughts, hurricanes, tropical storms, and other hazards. They also exacerbate stressors such as erosion and sea level rise. Global warming alters patterns of wet and dry seasons, creating atypical periods of intense rainfall and drought that disturb the ecosystems upon which residents depend.

Climate change is not only a meteorological problem, however. Racism, colonialism, elitism, savage capitalism, and other social injustices have created the conditions underlying the unequal impact of risk. In Latin America and the Caribbean, an estimated 103 million people live in informal settlements, and poverty and food insecurity have significantly increased since 2020. In turn, low-income residents generally depend on the informal economy for their livelihoods, live in settlements that are exposed to hazards, and have limited access to credit, land tenure, infrastructure, and services. Low-income women are typically more vulnerable to natural hazards than men. They have lower incomes, are less likely to own property, and often bear the double burden of generating income all the while caring for children and elderly family members. The combination of increased natural hazard exposure and vulnerability arguably explains why informal settlements are among the most disaster-prone areas in the world.

Bridging the implementation gap

Most scholars and international agencies now consider that adaptation to climate change effects is unavoidable. However, implementation of climate reaction plans and programs in Latin America and the Caribbean can be difficult—particularly in small- and medium-sized cities. Compared to large urban centers, small- and medium-sized cities have less infrastructure and capacity to offer basic services. They often operate with meagre budgets and lack technical, legal, and administrative resources to deal with housing and infrastructure deficits. Furthermore, and despite decentralization processes leading to an increase in local authorities’ responsibilities, adequate decision-making power, investment in administrative capacity, and financial resources have rarely accompanied these measures.

In addition to the problem of insufficient institutional capacity at the local level, climate adaptation and risk reduction policies formulated by central governments are often at odds with local needs and economic objectives. As a result, municipal officials and planners face difficult decisions, such as implementing relocation programs that residents actively oppose, zoning agricultural land for urban development, and protecting green areas that would otherwise be available for development.

In response to structural problems and policy contradictions, residents in informal settings often initiate, plan, and execute activities that help them cope with their daily struggles and to some degree, reduce risk. Informal settings are therefore effective incubators of culturally rich and informally driven responses to disasters and risks. However, these initiatives are sometimes ignored by decision- and policymakers, who may prefer to halt informal development, evict informal residents, and replace informal housing and commerce with green areas, master-planned urban development, infrastructure, or urban beautification initiatives. It is often fair to say that there is a significant implementation gap between top-down policies and local initiatives on the ground.

To address these issues, Artefacts built on ADAPTO to explore the following:

- How do local leaders and residents formulate and execute bottom-up initiatives to deal with climate change effects in informal settings?

- How do local rituals, practices, and existing (or missing) urban systems and regulations influence bottom-up initiatives?

- How does local leadership emerge in informal settings? How do stakeholder collaboration and community engagement take place throughout the implementation process?

- How can impact be amplified, ideas transferred across contexts, and solutions replicated and integrated into policy?

The research team was composed of more than 20 researchers from the disciplines of architecture, urban planning, engineering, social work, and social geography. It also included senior officers from Corporación Antioquia Presente, a Colombian NGO focused on disaster response activities in the region, as well as local actors and institutions.

In practice, the team decided not to be passive observers of the phenomena under investigation, but served as active agents in the transformation process. By working closely with local leaders, they were better able to follow their activities, gain their trust, and understand the dynamics of implementation from within. In all of the 22 studied cases, researchers provided leaders and participants with training and documentation on various topics, such as climate change trends, leadership, water management, hazard-proof construction, and sustainable gardening practices. In many cases, they also facilitated networking among local leaders, municipal officers, and other relevant stakeholders.

Main results

The 22 bottom-up initiatives served simultaneously as a research method and as a way to produce tangible change in informal settings. Thus, the research team created the “artefacts of disaster risk reduction”, exploring tangible objects and intangible spaces rooted in a deep understanding of the territory, local customs, and culturally relevant practices and rituals. These objects and spaces generated opportunities for open dialogue and established trust among citizens, local leaders, academics, business owners, and government officials. Most importantly, they allowed people in informal settings to reduce and manage the multiple risks they face.

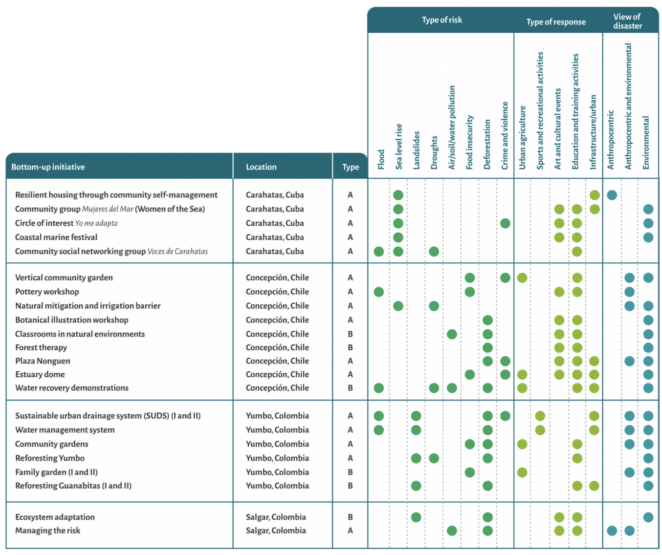

Local leaders and stakeholders designed and implemented the initiatives in response to multiple risks, including floods, food insecurity, sea level rise, landslides, erosion, water pollution, soil pollution, air pollution, heat waves, drought, deforestation, crime, and violence (see Table 1). They dealt with risk through culturally relevant activities in collective spaces, including construction, urban agriculture, recreational activities, art, education, and training. The initiatives focused on:

- Environmental protection and responses to the fragile relationships between people, the built environment, and ecosystems;

- Water management and consumption, including infrastructure for potable water, drains, reservoirs, and water collection;

- Protection of humans and the built environment from water-related hazards (floods, landslides, cyclones, tsunamis, droughts, and sea level rise); and

- Urban agriculture and food security.

Table 1. Local initiatives, including type of risk addressed and response deployed

Lessons Learned

- Adapting to global warming is not enough:comprehensive disaster risk reduction, based on recognition of social and environmental injustices, is required in informal settings in the region

- Trust between stakeholders is often basis for positive change.However, trust between governments and people living in informal settings is often elusive and fragile. Facilitative, structured dialogue, among other participatory approaches takes time, but can help break implementation barriers and establish common ground.

- Understanding people’s emotions in response to long-term risk, daily struggles, socio-economic concerns, disaster experiences and climate changeis key to recognising behaviours and social injustices, engaging in dialogue, mobilizing resources and driving change.

- Supporting and building on existing practices and activities,including those seemingly not linked to climate action per se, increases effectiveness and innovation in disaster risk reduction.

- Women typically lead change in informal settings,notably by creating the social fabric that allows disaster risk reduction to emerge. Supporting women in leadership roles is key to reducing social tensions and facilitating implementation.

- Academic and policy jargon rarely resonates with the needs and desires of people living in informal settings.Narratives grounded in local knowledge, ideas and practices do.

- Let emotions speak, drive and maintain climate action momentum.Red tape, contradictions in policy, and deficiencies in infrastructure render implementation difficult – even when there is well-written policy in place.

- Government investment and support are often fragile in informal settings.Universities and non-governmental organisations can play a crucial role in climate action as intermediaries between authorities and citizens.

- Limited means of communication and lack of information are major barriers to producing change in informal settings.Mobile technology allows local leaders and residents to connect, share knowledge and promote risk awareness.

- A clear ethical framework that considers issues of legitimacy, appropriate governance, trust and transparency is required for scaling impact.Bottom-up initiatives are difficult to replicate because they respond to local specificities. They require attention to detail, and careful and sustained efforts over long periods of time.

Suggested Citation (final technical report):

ADAPTO et al. (2021).Reponses to Risk and Climate Change in Informal Settings in Latin America and the Caribbean: The Importance of Bottom-up Initiatives and Structured Dialogue.Montreal: The Disaster Resilience and Sustainable Reconstruction Research Alliance –Œuvre Durable.

Suggested Citation (policy brief):

Dhar, T., Awan, R., Flórez Bossio, C., Walsh, E., Sherif, S. and Bornstein, L. (2021). Acknowledging Community Risk Perception in DRR Policies in Latin America: Three key lessons. https://artefacts.umontreal.ca/policy-briefs/

Related resources

- Artefacts of Disaster Risk Reduction

- Guardians of the Planet: Asia Pacific Children and Youth Voices on Climate Crisis and Disaster Risk Reduction

- Addressing Disaster Displacement in Disaster Risk Reduction Policy and Practice: A Checklist

- Strengthening institutional coordination & capacities – bonding climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction

- Foresight for policy & decision-makers

(0) Comments

There is no content