An investigation of the effects of PICSA on smallholder farmers’ decision-making and livelihoods when implemented at large scale – The case of Northern Ghana

Introduction

Helping smallholder farmers to adapt to, and cope with, climate change and variability is a key global challenge as outlined at COP21 in Paris. Critical farming and household decisions depend upon the weather, for example, how much rain falls, the length and start date of the rainfall season and the timing of dry spells.

The implications of a changing and variable climate mean that the role of climate services in agriculture is increasingly important. The growth of the climate services field has seen large scale investment in a wide range of initiatives to improve capacity.

The Participatory Integrated Climate Services for Agriculture (PICSA) approach has been developed through work in a number of sub-Saharan African countries since 2011 and it offers an approach that can be scaled across districts, countries and regions, and builds on extensive practical use of participatory methodologies with farmers.

This paper was published in the journal Climate Services on 22 March 2019 (online).

This case study is a summary of the report, for much more information please download the full paper from the right-hand column.

Methods

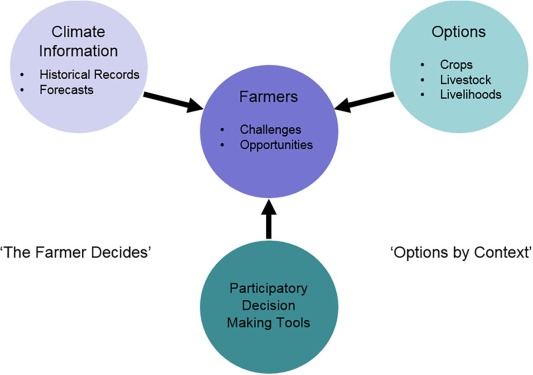

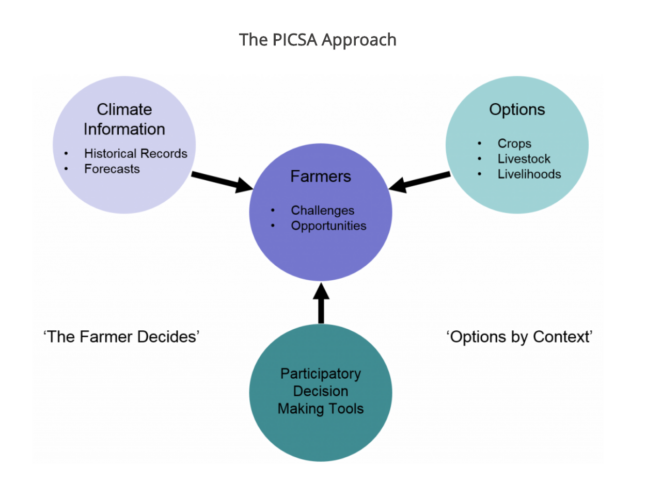

The PICSA approach focuses on supporting the farmer in their decision making and planning; hence they are at the centre of the figure. Farmers face both opportunities and challenges (e.g. markets, supplies, weather, pests, new innovations…). PICSA provides information on key challenges i.e. in this case climate and weather, and this includes not just forecasts but also historical climate information (top left of Fig.1). Improved information, understanding and analysis of climate information is of limited value without exploring the practical actions farmers can take. PICSA therefore includes identification and careful consideration by farmers of the range of options that they could take (top right of Fig.1) considered for crops, livestock and other livelihoods. A range of participatory decision making tools (bottom of Fig.1) enable farmers, collectively and individually, to explore and use the climate information, but very importantly to select and plan options that they wish to implement.

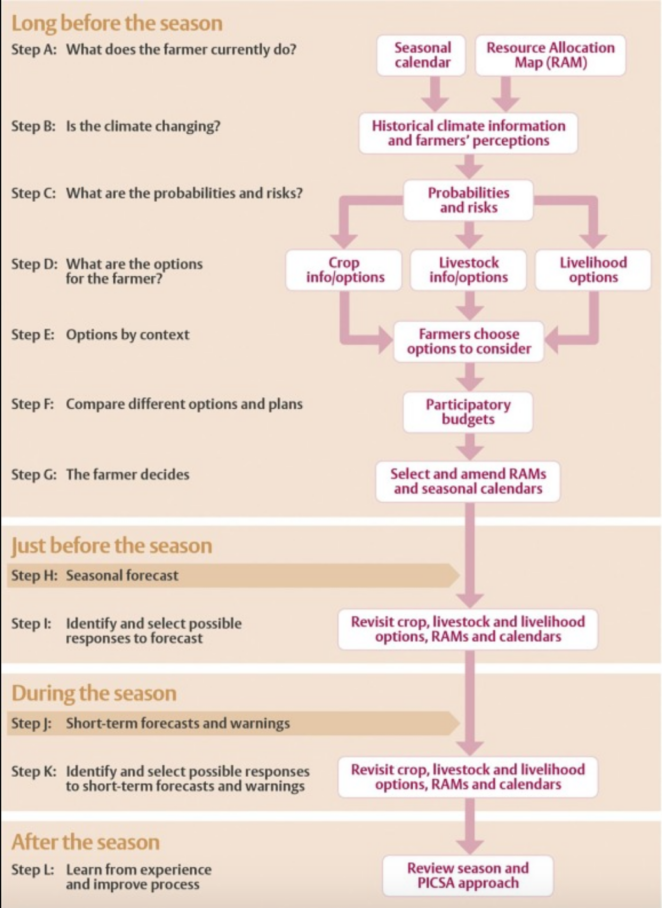

The approach is implemented by trained intermediaries (extension workers, NGO field staff, community volunteers) through a series of training sessions with groups of farmers. PICSA is designed for use with farmers irrespective of their level of literacy and has been successfully used with farmer who are non-literate. Intermediaries are encouraged to work with existing farmer groups rather than setting up new structures for the training. Within these sessions, trained intermediaries facilitate farmers to complete the twelve PICSA steps (Fig.2).

Results

Social and economic characteristics:- The data showed that there is no clear bias towards either gender in any of the wealth categories, though the wealthiest group has slightly more male respondents than the other three groups.

Training received and perception of usefulness of elements of the PICSA approach:-respondents reacted positively to the different tools and found them useful in their planning and decision making.

Are farmers making changes based on the PICSA approach?:-Respondents were, on average making three changes as a result of the training, with a range from no changes to ten changes and a median of three changes.

Crop enterprises:- The following examples illustrate types of changes that respondents were making in their crop enterprises.

- A new crop of soya beans

- A new variety of maze

- Changin the scale of a maize crop

Livestock enterprises:- The following examples illustrate types of changes that respondents were making in their livestock enterprises.

- Increasing the scale of a goats enterprise

- Changing the management of a sheep enterprise

Other livelihood enterprises:- The following examples illustrate types of changes that respondents were making in their other livelihood enterprises.

- Increasing the scale of a petty trading enterprise

- Increasing the scale of a charcoal selling enterprise

- Changing the management of a food crop selling enterprise

For more results please download full report on the right-hand column.

Lessons Learnt

Whilst it is not the focus of this paper to explore in detail the reasons why PICSA is stimulating innovation and behaviour change, we posit, drawing on observations from the work in Ghana and in other countries, the following:

(i) The emphasis on supporting farmers to make their own choices and decisions and providing them with the tools and information to do this;

(ii) Contextualisation – (a) Historical climate information provides locally specific evidence for farmers to help in their decision making and (b) the approach enables farmers to focus on their own farm and household context when considering challenges and opportunities and planning ahead;

(iii) PICSA is not just about information delivery but it is an integrated approach (a) taking a ‘whole farm’ approach and not simply concentrating on crops or livestock but acknowledging the farm as an integrated system, (b) bringing together Meteorological Services, Extension and farmers alongside other actors in the innovation system (seed suppliers, credit providers, NGOs etc…) and (c) that enables farmers and extension workers to engage with and use different and complimentary climate information in their planning and decision making (i.e. historical information, seasonal forecast and short term forecasts);

(iv) the approach provides a step-by-step framework for analysing and addressing complex issues and linking them to practical management options;

(v) information and tools are easily understood and easily shared by extension workers and farmers (including non and semi-literate) yet enable relatively complex analysis and planning;

(vi) the step-by-step approach helps extension staff to meet farmers needs/demands and to do their own jobs better;

(vii) by providing locally specific evidence and participatory tools for decision making the approach empowers farmers and emphasises the opportunity/ability to act rather than being passively impacted by the local climate; this empowerment also puts the responsibility on farmers rather than extension workers.

Suggested Citation

Clarkson, G., Dorward, P., Osbahr, H., Torgbor, F. and Kankam-Boadu, I. (2019). An investigation of the effects of PICSA on smallholder farmers’ decision-making and livelihoods when implemented at large scale – The case of Northern Ghana. Climate Services, 14, pp.1-14.

(0) Comments

There is no content