Assessing Climate Service Needs In Kaffrine, Senegal: Livelihoods, Identity, And Vulnerability To Climate Variability and Change

Introduction

For those whose livelihoods revolve around rain-fed agriculture, climate services have the potential to reduce precipitation- and temperature-related risks to agricultural production, boost agricultural yields by enabling appropriate crop and variety selections, and build resilience in rural populations by enhancing the food and income base of their livelihoods (e.g. Hansen, Baethgen, Osgood, Ceccato, & Ngugi, 2007; Klopper, Vogel, & Landman, 2006). To achieve these lofty potentials, climate services must deliver information that is salient, legitimate, and credible to those for whom these services are designed and to whom they are targeted (e.g. Carr & Owusu-Daaku, 2015; Hansen, 2002; Peterson et al., 2010; Roncoli et al., 2009; Waiswa, Mulamba, & Isabirye, 2007). Further, we must understand if and how new information is of value to these users. Information that is not actionable, which does not speak to farmer needs, or which lacks credibility relative to other sources of weather and climate information does not add value to their decision-making, and may even result in confusion around decision-making that reduces the efficacy of existing livelihoods strategies. In short, it is becoming clear that weather and climate information is not inherently valuable to those in rural agrarian contexts, but must be tailored to the specific needs of the users if it is to have a productive impact on their lives and livelihoods (Carr & Owusu-Daaku, 2015; Carr, 2014a).

This report is available to download (see link in right-hand column).

Methods and Tools

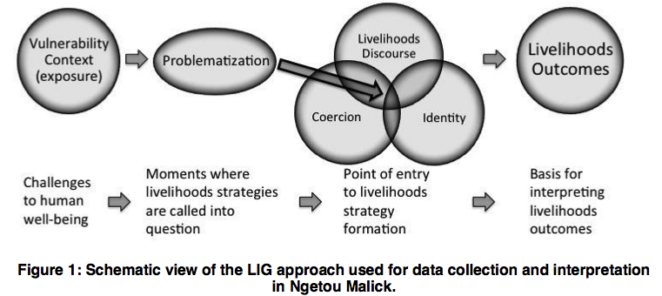

To explore the livelihoods decision-making of the residents of Ngetou Malick, and of Kaffrine more broadly, the Humanitarian Response and Development Lab (HURDL) team employed the Livelihoods as Intimate Government (LIG) approach (see Figure 1 below, from p.3 of the report). This approach views livelihoods not merely as activities undertaken to make a living in a particular place, but as wider efforts to order the world. These efforts result in the procurement of material needs, but also the identification and reinforcement of social roles, and the establishment of appropriate activities and actions for different members of the community.

LIG is both a conceptual framework and a methodology for studying livelihoods decision-making. Following Carr (2014b), the field team began work by establishing the vulnerability context of Kaffrine with a basic literature review, and two weeks of preliminary scoping fieldwork in two villages in rural Kaffrine. Fieldwork in Ngetou Malick built on this preliminary understanding of the vulnerability context, using semi-structured interviews to explore the vulnerabilities of 44 residents.

Vulnerability in Ngetou Malick (in brief)

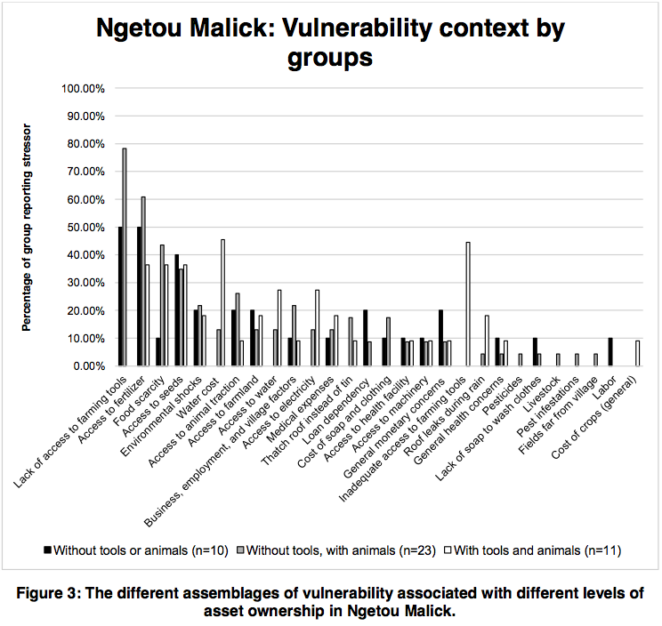

Individuals within Ngetou Malick are exposed to numerous pressures including environment stresses and shocks, inadequate access to livelihoods resources, and economic factors. The primary stressors within the overall vulnerability context in Ngetou Malick center around agricultural livelihoods and access to agricultural livelihoods resources. As agriculture is the primary livelihood for all of the 44 individuals within the interview set, this is not surprising.

Though many individuals report the same stressor as a part of their individual vulnerability context, the assemblage of vulnerabilities reported by individuals tended to cluster into three groups (see Figure 3 below, from p.6 of the report).

Different farmers, different goals: Opportunities for advisories in Ngetou Malick and beyond (in brief)

The discussion of identity, livelihoods, and vulnerability in the report (download in right-hand column) suggests that there are ten different categories of farmers in Ngetou Malick. These categories reflect the different vulnerabilities seen in this community, and speak to different needs and opportunities for climate services. Below, is a summary of the different opportunities and challenges associated with climate services for different types of farmer in the community (please see the report for more detail). This exercise serves to illustrate who would benefit from what sorts of services, helping to shape future service design, and clarifying the likely impacts of particular services.

Junior men without animals and tools

- Reasons to use advisories: Improve millet and maize yields to provide more food for the household; improve peanut yields to acquire more income and fodder; increase agricultural productivity; reduce costs of agriculture and the risks associated with relying on uncertain weather information for planting;

- Barriers to use: Limited authority over plowing or planting time for crops; limited control over the allocation of their labor

Women without tools (includes those with and without animals)

- Reasons to use advisories: Improve peanut, bissap, and cowpea yields to provide more cooking ingredients for the family and to garner more personal income.

- Barriers to use: No authority over plowing or planting time for crops; inadequate time to focus on agricultural pursuits due to a multitude of household duties; much time spent working in husbands or relative’s fields;; no guarantee of land ownership or seed provision season by season.

Junior men with animals but without tools

- Reasons to use advisories: Improve millet and maize yields to provide more food for the household; improve peanut yields to acquire more income and fodder; increase agricultural productivity; reduce costs of agriculture and the risks associated with relying on uncertain weather information for planting; improve yields of sorghum and cowpea for use as animal fodder;

- Barriers to use: Limited authority over planting time for crops; limited control over the allocation of their labor

Senior men with animals but without tools

- Reasons to use advisories: Improve millet and maize yields to provide more food for the household; improve peanut yields to acquire more income and fodder; increase agricultural productivity; reduce costs of agriculture and the risks associated with relying on uncertain weather information for planting; improve yields of sorghum and cowpea for use as animal fodder; maintain social status within community;

- Barriers to use: Limited access to farming tools makes it difficult to control the timing of planting

Junior men with animals and tools

- Reasons to use advisories: Improve millet and maize yields to provide more food for the household; improve peanut yields to acquire more income and fodder; increase agricultural productivity; reduce costs of agriculture and the risks associated with relying on uncertain weather information for planting; improve yields of sorghum and cowpea for use as animal fodder; make variety selections to respond to price opportunities in the markets for millet, maize, and peanuts

- Barriers to use: Limited authority over planting time for crops; limited control over the allocation of their labor

Senior men with animals and tools

- Reasons to use advisories: Improve millet and maize yields to provide more food for the household; improve peanut yields to acquire more income and fodder; increase agricultural productivity; reduce costs of agriculture and the risks associated with relying on uncertain weather information for planting; improve yields of sorghum and cowpea for use as animal fodder;

- Barriers to use: None

Senior men are the members of the community ablest to act on seasonal weather and climate information. The utility of such information for senior men in this group would likely be greatest in informing crop selection and input application decisions. Most of these men describe in detail the various methods that they use currently to determine proper planting time (setting basins on roof, digging holes in soil, checking soil for dampness, waiting for first rain, using a rain gauge etc.). Therefore, they are unlikely to use advisories to inform their planting decisions. However, so long as the information speaks to length of season and distribution of precipitation in the season, it should add value to the sources of information currently used by these men.

Authors & contributing organisations

| Personal Author(s): | Edward R. Carr Grant Fleming Tshibangu Kalala |

| Authoring Organization(s): | University of South Carolina Humanitarian Response and Development Lab Engility Corp. International Resources Group (IRG) |

| Sponsoring Organization(s): |

(0) Comments

There is no content