Using OPAL surveys to assess local water quality in the UK

This case study is part of the SEI Urban Toolbox for Liveable Cities which has been developed by the SEI Initiative on City Health and Wellbeing. The Urban Toolbox is a collection of tools, developed within SEI or in coordination with SEI, aimed at supporting planning and decision-making for improving the health, well-being and resilience of city residents and urban systems more broadly. It demonstrates how citizen science approaches, like the OPAL survey, can be used to investigate the relationships between water quality and urbanisation.

Introduction

Surprisingly little is known about the quality of many of the UK’s fresh water bodies. Ponds, rivers and lakes support a huge variety of plants and animals, and us too. Good water quality is essential for a functioning, healthy ecosystem. However, water is easily affected by pollutants from the air and on land. The aim of the OPAL Water Survey was to provide a national ‘snap-shot’ assessment of water quality for as many lakes and ponds across the UK as possible, and, in doing so, to improve education and awareness of aquatic environments.

This Urban Toolboxcase study is an abridged version of the original text, which can be downloaded from the right-hand column. Please access the original text for more detail, research purposes, full references, or to quote text.

Method

Survey design:

The Water Survey includes four activities to help participants build a picture of water quality in their local environment:

- Measuring water clarity – using the OPALometer

- Measuring water pH using a dip-strip

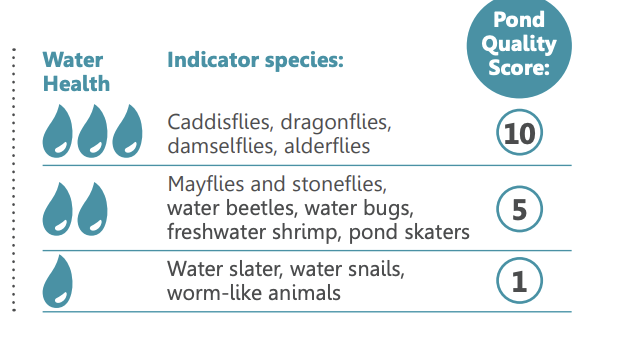

- Recording the presence or absence of aquaticinvertebrate ‘indicator species’

- Recording the presence or absence of amphibians,dragonflies, damselflies and duckweed

Indicator species are those whose presence, absence or relative abundance in an environment is a sign of the ecosystem’s overall health. Indicator species have been used to assess water quality for over 100 years. They are easy to sample and identify at a broad classification level, making them well suited to public studies, especially with children.

The use of public participation allowed access to many more lakes and ponds than would be possible by traditional monitoring programmes, including some in private grounds that had never been surveyed before. A water survey ‘pack’ was compiled that included a series of activities and materials, with the aim of providing something of interest to as many people as possible whilst generating useful data. 40,000 packs were printed and freely distributed. All materials were (and remain) freely available to be downloaded from the OPAL website. Both biological and non-biological assessments were included in order to stress the importance of considering lakes and ponds in an holistic way.

Quality control:

As with all OPAL survey materials, the OPAL Water Survey activities were pilot tested with ‘naive audiences’ in order to ensure clarity of the step-by-step approaches and survey forms. Such an approach is crucial for untrained volunteer surveys. An additional quality control step was added for those submitting their survey results on line, in the form of a picture-based quiz of freshwater invertebrates. Records associated with incorrect quiz answers were then marked so those analysing the results could choose to exclude them or not.

All instructions and protocols for undertaking the survey activities and submitting information (either directly online or Freepost return of paper copies for participants who had no internet access) were present within the pack. Once data had been entered onto the OPAL website, anyone with internet access was able to interrogate and explore all submitted data using a variety of online tools, data mapping and visualization techniques.

Key Findings

The OPAL Water Survey results provided a regional and national assessment of water quality as well as a first national picture of water clarity (a measure of suspended solids concentrations). Rose et al.(2016) reported that less than 10 % of lakes and ponds surveyed with the OPAL Water Survey were ‘poor’ quality while 27 % were in the highest water quality band.

Health scores from all categories were present in both urban and rural sites in each region of the UK. The high pond health scores reported for these sites show that both natural and artificial ponds, in rural and urban settings, can have a high aquatic diversity.In particular, the value of these ponds lies in the varied habitats they can provide, highlighting the need to sample in as many habitats as possible for a more reliable and repeatable pond health score, particularly in lowland sites where lakes may have a greater number of habitat types.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Overall, the simple sampling and identification methods, as used in the OPAL Water Survey, were found to allow the collection of repeatable results, particularly where multiple habitats were sampled and summarised in a single pond health score (Rose et al.,2016). Although there will always be inherent uncertainty in data collected by untrained volunteers, the application of quality control at all survey stages (design, identification tests, data submission and interpretation) can help increase confidence in the quality of generated data. Furthermore, results allowed an exploration into spatial trends, such as differences between rural and urban areas. This approach can thus be transferred to and used in other areas to assess the influence of urbanisation on water body quality.

This survey was led by water quality researchers at University College London, with support from the Natural History Museum, London and the Field Studies Council. If you wanted to develop a similar survey for your country, reach out to biologists who know about benthic (bottom dwelling) macro-invertebrates (macro meaning big enough to see without a microscope). You might also like to look atFreshwater Watch to see if there are any existing groups local to you.

Suggested Citation:

For the report:

OPAL (2016). OPAL – Exploring Nature Together: Findings and Lessons Learnt.Available at: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/research-centres-and-groups/opal/Findings-and-Lessons-Learnt-Report—2016-compressed.pdf

For the journal paper:

- Rose, N.L.,Turner, S.D., Goldsmith, B.,Gosling, L.,and Davidson, T.A. (2016) Quality control in public participation assessments of water quality: the OPAL Water Survey,BMC Ecology,16: 23-43, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-016-0063-2

Related resources

- Open Air Laboratories (OPAL) surveys

- Using OPAL surveys to explore the effects of urbanisation on invertebrate biodiversity in the UK

- Freshwater Invertebrate Identification Guide (UK)

- The OPAL Water Survey Booklet

- Citizen science for monitoring air pollution

- Using citizen science to monitor particulate matter pollution in an informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya

(0) Comments

There is no content