Using citizen science to monitor particulate matter pollution in an informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya

This case study is part of the SEI Urban Toolbox for Liveable Cities which has been developed by theSEI Initiative on City Health and Wellbeing. The Urban Toolbox isa collection of tools, developed within SEI or in coordination with SEI,aimed at supporting planning and decision-making for improving the health, well-being and resilience of city residents and urban systems more broadly. It demonstrates how a citizen science approach can be used to assess air quality in an urban area.

Introduction

Outdoor air pollution is a major environment and health issue, and a policy challenge in both developed and developing countries. One of the air pollutants of concern for human health is fine particulate matter (specifically PM2.5).

Informal settlements are often found in close proximity to industrial plants, busy roads and dump sites. They often have dusty dirt tracks and intensive use of biomass fuels or kerosene for cooking and heating means these residents may be exposed to a very different mix of pollutants to those measured by the regulatory monitoring stations. Nairobi has a population of 3.1 million (2009) of whom an estimated 60% live in around 200 informal settlements.

The rise of ‘citizen science’ approaches in the last few decades (Bonney et al., 2014), combined with the development of a new generation of air quality monitors providing continuous records of pollitants, offers new opportunities to actively engage communities with the highest health burdens from air pollution in monitoring their local environment and identifying measures that might reduce their exposure.

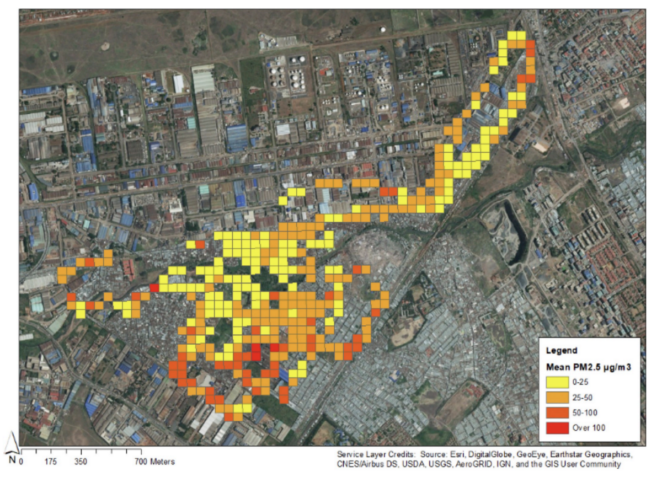

This case study describes what the authors believe is the first study in a major African city to actively engage the community of an informal settlement in monitoring and mapping the air pollution within it, linking this directly to their perception of issues, and to the air pollution policy framework in Nairobi. The work was carried out within one informal settlement in Nairobi, with PM2.5 measurements made in September and October 2015.

*This Urban Toolbox case study is an abridged version of the original text in the open access paper “Particulate matter pollution in an informal settlement in Nairobi: Using citizen science to make the invisible visible”published in Applied Geography, 114, under the CC By 4.0 license in January 2020 © West et al. For much more detail, research purposes, full references, and to quote text you can access the paper from the right-hand column.

Methodology

There were three interlinked elements to the research: particulate matter monitoring, a questionnaire (conducted before and after the monitoring campaign in order to assess any changes in knowledge during the campaign) and two workshops.

Study site:

The study was carried out in Mukuru, as we were approached by Muungano Wa Wanavijiji (MWW) (affiliated to Slum Dwellers International), an organisation with a long history of working in the area, who had received multiple complaints from residents about air pollution, and MWW wanted monitoring to take place.

Monitoring:

Three battery-powered low-cost particle counters (Dylos) were used for the personal monitoring campaigns, and community members themselves chose where to monitor. In order to convert the Dylos particle number concentrations to PM2.5 mass concentrations and to cross-calibrate the Dylos sensors, the three sensors were run, for a period of 3 days (23rd-25th October 2015), alongside a Mobile Air Pollution Laboratory owned by the Kenya Meteorological Department, which functions as a regulatory monitor and uses a GRIMM Aerosol Technik Environmental Dust Monitor model 180.

Six community champions were selected to carry the monitors. MWW selected champions who were settlement residents and who had a variety of occupations, in order to sample a range of places and jobs within the informal settlement. They consisted of a roadside vendor (female), a door to door grocer (male), a second-hand clothes hawker (female), two people involved in community development work (female), and a young person involved in a community clean-up campaign (male). The community champions were trained how to handle the equipment used in the study and given a one page set of instructions on how to operate it.

The target was to record at least 5 h of data in the morning cycle and at least 3 h in the evening cycle making a total of up to 8 h per day. Alongside a GPS tracker, champions were asked to keep a handwritten activity log detailing where they were in the settlement every few hours, and whether they were indoors or outdoors. Every 2–3 days the champions met the fieldwork project coordinator to download the data onto a PC. After the monitoring campaign finished, three community champions walked around the settlement with a GPS tracker noting the locations of potential sources of pollution.

Questionnaire:

Respondents of the structured questionnaire included street vendors, restaurant owners, shop owners, carpenters, factory workers and housewives. The perception surveys were conducted by six research assistants recruited by MWW from the local community, each of whom was paired with an experienced researcher. These research assistants had experience of working with MWW, had previously conducted surveys in the community, and were trusted in the area. The research assistants were trained how to administer the questionnaire.

The survey was conducted first in September 2015 at the beginning of the project and then repeated in November 2015, in order to assess any changes in perception throughout the project.

Workshops:

A project inception workshop was held on September 15, 2015 with 40 stakeholders from the local community, local administrators and national and county government officers, researchers, individuals from civil society organisations and our research assistants and community champions.

An end of project workshop was held on 5th December 2015, with 47 participants who included community representatives from the informal settlements, officers from government agencies (the National Environment Management Authority, National Council for Science and Technological Innovations and Kenya Meteorological Department), representatives from UN agencies (UN Environment Programme and UN Habitat), researchers and academics from Kenya (University of Nairobi and Africa Population and Health Research Center) and abroad (Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) York, University of Gothenburg, UC Berkeley), a representative from Media for Environment, Science, Health and Agriculture (MESHA) and medical experts from the Nairobi County Government.

Data analysis:

Data was coded to be ‘indoor’ or ‘outdoor’ based on the GPS and activity logs. Statistical analysis of PM2.5 exposure data was carried out using the R analytical software (build 3.2.2), and the “MASS” package.

Outcomes and Impacts

- The study found significant differences in PM2.5 exposure between individual workers that could be partially explained by spatial differences in concentration that we identified within the settlement.

- Residents of the informal settlement identified a number of sources that might explain these differences in concentration, although many residents perceived air quality to be good both indoors and outdoors.

- The workshops raised awareness of the issue of air pollution and brought together affected community members and local and national policy makers to discuss air pollution issues in Nairobi’s informal settlements.

- As a result, a new knowledge exchange network, the Kenya Air Quality Network, of policy-makers, researchers and community members was formed with the aim to facilitate the improvement of air quality across Kenya.Ever since, the KAQN has met regularly, with SEI Africa acting as its secretariat. Since 2016, public health agencies have become involved in the network and industry representatives have been invited to annual conferences; engaging these parties will further enhance the impact of the network.

- The formation of the KAQN as a result of this project has helped to drive research and action forwards, not just in this settlement, but in Kenya and neighbouring countries more widely. To date, three further action-oriented research projects on the topic of air pollution in Mukuru have been funded, with the KAQN helping both steer the direction of the research and act as a mechanism for enacting change as a result of project findings.

This study showed that a citizen science approach, commonly used in the ‘global North’, can be applied to settings such as informal settlements.

Suggested Citation:

West, S.E., Büker, P., Ashmore, M., Njoroge, G., Welden, N., Muhoza, C., Osano, P., Makau, J., Njoroge, P. and Apondo, W. (2020). Particulate matter pollution in an informal settlement in Nairobi: Using citizen science to make the invisible visible. Applied Geography, 114, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2019.102133

(0) Comments

There is no content