How to involve stakeholders

How do you involve stakeholders?

See also Social learning and Participatory Processes especially the section in Participation and Power

Ravetz, (1997) states ‘policies for managing sustainability will be effective only if they have the moral support of the great mass of people’. This suggests that participatory processes should be used as a way to democratise science and empower citizens. Others see it more as a way to inform policy making and as advising in decision-making processes.

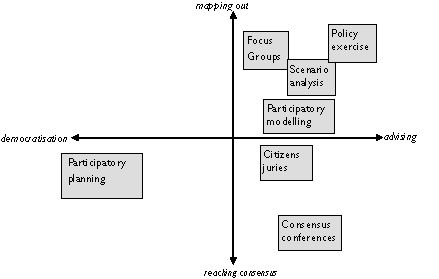

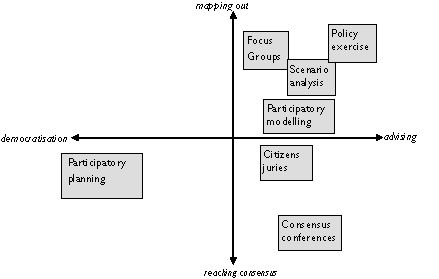

van Asselt et al, (2001) describe four possible goals of participatory processes:

- Mapping out diversity – ways to discover the diversity of opinion on a subject or test reactions to a strategy in a contained environment

- Reaching consensus – methods that seek to define one option or decision

- Democratisation – methods that enable participants to use their own knowledge and experience to create options for tackling (policy) issues that directly concern them.

- Advising – methods which are used to reveal stakeholders knowledge, values and ideas that are relevant to the process of decision-making

The figure below gives a categorisation of participatory methods (van Asselt et al (2001)). This focuses on participation imposed by scientists. The upper left quadrant is empty as these techniques are more associated with participatory processes organised by stakeholders themselves. The position of the techniques as the goals may be defined differently by different users.

Stakeholders each have different information and perceptions of an issue. In looking a the impact of climate change in an area and how people might adapt local people have valuable knowledge about the locality, the history, who are the most vulnerable and how they have coped in the past. Scientific knowledge is needed e.g. in the case of arsenic contamination in Bangladesh. Scientific techniques were required to identify the problems and a knowledge of the geology of the land but it was human factors that made the problem. Understanding these human factors, and lay people’s perceptions of the problem, will lead to the solution.

Glicken, identifies 3 types of information:

- Cognitive: based on technical expertise, presented by scientists in factual arguments about issues such as the extent of damage, methodologies

- Experiential: based on personal experience and common sense

- Values-based: based on perceptions of social value, moral codes, the ‘goodness’ of a particular activity

The process of stakeholder participation does not substitute lay knowledge for scientific knowledge but uses them differently. Citizens, interest groups and business, for example, are participants who express values, preferences and contribute to the non-scientific knowledge. Representatives of governmental institutions and scientific experts are not always actively involved in the process. Their roles differ according to the techniques used. For example by providing information via a report or testimony or being actively involved in the discussions as full participants.

Techniques aimed at Discovering Diversity of Opinion (from van Asselt et al, 2001)

Focus Groups Goal: to uncover diverse information about values and preferences pertaining to a defined topic and why they are held by observing the structured discussion in an interacting group. A focus group is a planned discussion in a small group (4-12) of stakeholders facilitated by a skilled moderator. It is designed to obtain information about preferences and opinions in a permissive, non-threatening environment. Group members influence each other by responding to ideas and comments in the discussion, with the consequence that a more natural articulation unfolds. In focus groups scientists play the role of facilitator or observer. They are not usually involved as full participants.

In one-to-one interviews it is assumed that individuals know what they feel and that they form ideas in isolation. When a new idea is being tested or the issue is controversial social scientists have noted that people often need to listen to other opinions before they form their own viewpoint. Also, during the course of a discussion the opinion of an individual may shift. The focus group thus enables viewpoints that might not have come forth in individual interviews and allows analysis of what might influence shifts in opinion.

Groups members are generally strangers to each other but all have something in common as this has been shown to make them more likely to communicate freely. Being strangers they know that they are unlikely to see each other again and so are less inhibited about sharing their thoughts and opinions.

Scenario Analysis Goal: to explore the range of available choices involved in preparing for the future, test how well those choices would succeed in various possible futures and prepare a rough timetable for future events.’ (Fahey and Randall, 1998)

Scenario analysis engages stakeholders in creating and exploring scenarios of the future in order to learn bout the external environment and/or understanding the decision-making behaviour of the organisations involved. The free-format approach enables the exchange and synthesis of ideas and encourages creative thinking. This method is most appropriate for addressing complex issues and uncertain futures, where decision-making is generally based on non-quantifiable factors and where a it is important to establish a dialogue between the key actors in order to plan for the future.

Typically all stakeholders, including decision-makers and scientists will be actively involved in the process. Key issues or questions relevant to the subject are identified. From this key trends and driving forces can be determined. These may then be prioritised to determine which are the most important or uncertain. These strands may then be fleshed out tracing the narrative line from a beginning to an end. Following the initial workshop there may be a period of reflection where trends and indicators developed for the different scenarios may be tested for robustness and plausibility.

Visioning Goal: to bring together different stakeholders and to stimulate them to put forward their view of they would like their future to be and their role in creating that future. In a visioning workshop the participants may be presented with a set of possible futures (scenarios of life at a defined point in the future) or may be asked to create their own, first as individuals then as a group, through establishing common ground. The group is then asked to address barriers to achieving these visions and ways that these barriers may be overcome. A process of ‘backcasting’ may then be used to bring the group back to the present day. From there it is possible to identify steps that may be taken today to reach the ideal future.

Policy Exercises Goal: to integrate knowledge from different sources, explore alternative future developments and evaluate new policy ideas in order to develop a better structured view of complex problems. Policy exercises aim to identify poorly understood topics and questions and make discoveries, to increase problem solving but not provide solutions. Geurts and Duke, 1999.

A policy exercise is a creative process in which games or models are used to explore alternative futures. It is a good way to get information about human behaviour and human interactions in negotiations. Participants are given a simpler version of a complex policy issue or system and asked to assume roles or play the game in order to think through the operation of the issue. As the participants are out of their normal working environments and the situation used is a hypothetical one they are stimulated to think freely and creatively. This can help the observers to clarify the goals and objectives of a proposed policy and think about how it might be implemented.

Policy exercises usually involve direct interaction between stakeholders and policy makers and scientists. The exercises usually take to form of games, simulations, structured workshops or computer models. A great deal of time and thought is thus needed in their preparation as they are intended to represent behaviour in complex situations. The models are used to support rather than to guide the discussions. Overemphasis on the models can cause a stumbling block to creative, exploratory thinking. The challenge it to create a realistic situation which inspires the participants to play their roles.

Techniques Aimed at Building Consensus

Participatory Modelling The term ‘participatory modelling’ or group modelling refers to the active involvement of model-users in the modelling process (which could be a conceptual model or a computer model). It is useful in building a mutual understanding between scientists, stakeholders and policy makers. The process aims to build consensus between the various groups.

Participatory Planning The main goal of World Bank participatory planning techniques is to: ‘level the playing field between different levels of power, various interests and resources and to enable different participants to interact in an equitable and genuinely collaborative basis. To achieve a shared decision (or consensus), build up commitment to and ownership of this decision, and empower individuals to address problems which affect them.

World Bank Participatory planning tools enable participants to influence and share control over development initiatives and decisions affecting them. The tools promote a sharing of knowledge and, through ownership of the process a sense of commitment to the outcomes that empowers the group to develop more effective strategies.

The process can engage high level decision-makers, experts, representatives of interest groups and NGOs as well as citizens. It is vital to get the big players on board in order not to alienate them or provoke opposition. It is also important to engage the citizens as they are often left out of such decision making on issues that directly affect them.

There are many techniques (mapping, ranking, timelines) that can be used and often a number may be used together in one event. A map may be used to brainstorm ideas initially. Ideas resulting from this may them be prioritised. The top issues may then be ‘action planned’ to identify who will be affected by the proposed decision – who will help and who will hinder the process. These groups (if not already present) can then be engaged to move the process on.

Consensus Conferences Goal: to broaden the debate on issues of science and technology to include the view points of non-experts. The aim is to arrive at a consensus opinion on which policy decisions can be based. A consensus conference is a public enquiry centred around a group of citizens who are charged with the assessment of a socially controversial topic of science and technology. These lay people put questions to a panel of experts, assess the experts answers and then negotiate amongst themselves. The result is a consensus statement which is made public in the form of a written report directed at parliamentarians, policy makers and the general public that expresses their expectations, concerns and recommendations at the end of the conference.

The lay panel have no vested interests in the issues but have been chosen to represent different attitudes towards the issue. The group is balanced on age, gender, education, occupation and area of residence.

Citizen’s Juries Goal: ‘to incorporate knowledge of the type that is usually absent in decision-making processes by creating the conditions for informed political deliberations between a representative group of citizens’ Smith and Wales, 1999

Citizens juries are based on the rationale that given adequate information and opportunity to discuss an issue, a group of stakeholders can be trusted to make a decision on behalf of their community, even though others may be considered to be more technically competent. Citizens juries are most suited to issues where a selection needs to be made from a limited number of choices. The process works better on value questions than technical issues.

The jury is made up of a number (12-24) of stakeholders (with no special training) who listen to a panel of experts (‘witnesses’) who are called to provide information related to the issue. The stakeholders are chosen at random from a population appropriate to the scale and nature of the problem. Selection is based on several characteristics largely gender, education, age, race, education, geographic location and attitude to the question in hand. The group is supposed to represent a microcosm of the community including its divers interests and sub groups. There are some doubts as to whether such a small group can really be representative of the diversity of opinion in the larger community. Does a middle-aged woman represent all middle-aged women? Some think it can only represent the community in a symbolic sense.

Experts are chosen by a panel with no interest (or stake) in the outcome. They represent a several points of view and additional experts can be called by the jurors to clarify points or to get extra information.

Related Pages

Introduction to Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement

(0) Comments

There is no content