Gender-Responsive National Adaptation Plan (NAP) Processes: Progress and promising examples

Introduction

This report is the third in a series of synthesis reports developed by the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) Global Network that assess progress on gender-responsive approaches in NAP processes at the global level. It comes at a time when countries have continued to make progress in advancing their NAP processes despite the overwhelming impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. It coincides with the midpoint of the Gender Action Plan under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), making this a good moment to reflect on progress in integrating gender considerations in NAP processes. The report explores this through a systematic review of the NAP documents submitted to the UNFCCC, as well as through practical examples that illustrate how countries are taking a gender-responsive approach to their NAP processes.

This weADAPT article is an abridged version of the original NAP Report, which can be downloaded from the right-hand column. Please access the original text for more detail, research purposes, full references, or to quote text. The Report is also available in both French and Spanish.

Gender-responsive approaches:

Gender-responsive approaches are ones that actively promote gender equality by addressing gender norms, roles, and inequalities (NAP Global Network & UNFCCC, 2019; World Health Organization, 2009). Adopting a gender-responsive approach typically involves consideration of three sets of key questions (NAP Global Network, 2019):

- How do people’s needs and capacities for adaptation differ? Why do these differences exist?

- Who has a voice in adaptation decision making? Who is left out?

- Who will benefit from investments in adaptation? Who may be left behind?

Methodology

The analysis presented in this report draws on two key sources of information:

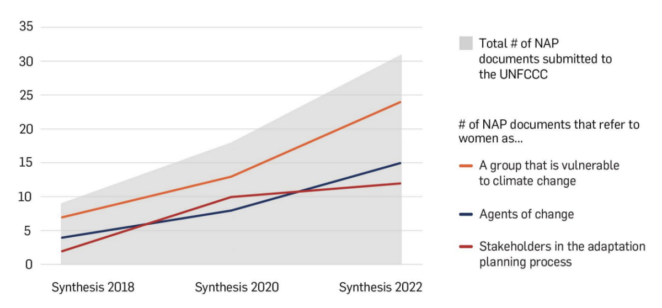

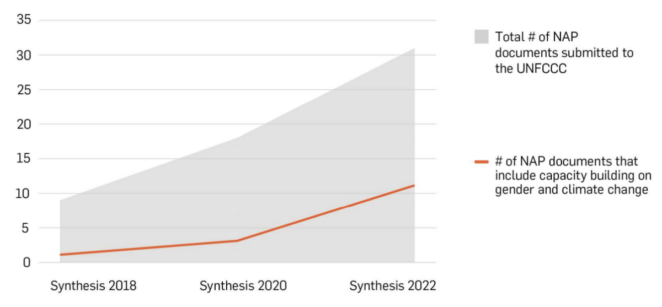

- Systematic review of NAP documents: Over the 4 years since our first synthesis report, the number of NAP documents that have been communicated to the UNFCCC has more than tripled, from 9 to 31. Using the same methodology applied in our previous synthesis reports, we have systematically reviewed these documents, providing a basis for assessing progress since our first synthesis report in 2018. The findings from this assessment are presented in Section 5. Appendix 1 provides an overview of the specific results, as well as a list of the countries that are included in the sample.

- NAP Global Network country engagement: As of March 2022, the NAP Global Network has provided technical support for NAP processes to more than 50 countries, with 16 of these receiving support specifically on integrating gender considerations. This engagement provides us with important insights into the different activities countries are undertaking as they move through their NAP processes. We draw on the knowledge and learning gained from our support to country NAP processes to share promising examples of progress in Section 6, recognizing that this is only a snapshot of the broader progress that is occurring on gender-responsive NAP processes.

Key Findings

Document review:

When it comes to NAP documents, we observe progress in the following areas:

- Framing of gender issues: More countries are referring to gender equality and gender-responsive approaches in their NAP documents, along with other concepts that may provide entry points for an intersectional approach, such as inclusion and human rights.

- Positioning of women: Though there are still a larger number of NAPs that position women as a particularly vulnerable group, we are seeing more and more where the potential of women as agents of change in adaptation is recognized.

- Use of gender analysis to inform adaptation planning: An increasing number of NAP documents show evidence that gender analysis has been used to inform the framing of adaptation issues, or to make the case for the consideration of gender issues in implementation.

- Consideration of gender in institutional arrangements for adaptation: The inclusion of the ministry responsible for gender in the institutional arrangements for adaptation is indicated in an increasing proportion of the NAP documents, either as part of coordination mechanisms or as responsible for implementing particular actions.

- Capacity building on gender and adaptation in the NAP process: The need for targeted capacity development on gender and adaptation is receiving more attention in recently submitted NAP documents, with a focus on both government actors and, in some cases, nongovernmental stakeholders.

- Integration of gender considerations in adaptation monitoring and evaluation: There is increasing recognition in NAP documents that gender considerations must be integrated into adaptation monitoring and evaluation, through specific indicators and the collection of disaggregated data, among other approaches.

Practical examples:

Beyond the documents, there are a number of promising examples where countries have taken concrete steps to integrate gender considerations into their NAP processes:

- The Central African Republic and Chad have undertaken targeted gender analyses to inform their NAP processes, with the latter focused on exploring the role of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours related to gender in advancing gender-responsive NAP processes.

- In Ghana and Kenya, visual storytelling has provided a basis for dialogue on adaptation among national-level decision-makers and women on the front lines of climate change.

- The ministries responsible for environment and gender in Côte d’Ivoire signed a memorandum of understanding to formalize their collaboration on gender and climate change.

- Training for government actors in the Republic of the Marshall Islands and the Dominican Republic has enhanced capacities for gender-responsive approaches in their NAP processes.

- While in Suriname, gender has been integrated into the monitoring, evaluation, and learning framework for the water resources sector adaptation plan.

Conclusion

In our 2020 synthesis report, we pointed to the transformative potential of the coming years in terms of advancing gender-responsive and socially inclusive approaches to adaptation. While there is still a long way to go, there are many things to be celebrated in this review of progress.

This progress demonstrates the potential of NAP processes as a mechanism for ensuring that climate action addresses gender and social inequalities. This potential comes from their participatory, cross-sectoral, and iterative nature, as well as the fact that they are focused on medium- and longer-term planning, recognizing that social contexts are dynamic and that systemic change takes time. As countries increasingly move from planning to implementation of adaptation actions, more opportunities are created to work with diverse stakeholders to build resilience while also creating more equitable communities and societies.

Suggested Citation:

Dazé, A., & Hunter, C. (2022). Gender-responsive National Adaptation Plan (NAP) processes: Progress and promising examples (NAP Global Network synthesis report 2021–2022). International Institute for Sustainable Development. www.napglobalnetwork.org.

Related resources

- Towards Gender-Responsive National Adaptation Plan (NAP) Processes: Progress and Recommendations for the Way Forward

- Toolkit: Facilitating a gender-responsive NAP process

- Conducting Gender Analysis to Inform National Adaptation Plan (NAP) Processes: Reflections from six African countries

- Toolkit for a Gender-Responsive Process to Formulate and Implement National Adaptation Plans (NAPs)

(0) Comments

There is no content