Monitoring and Evaluation Toolkit: Participatory Video and the Most Significant Change for facilitators

Introduction

InsightShare‘s Years of experience in using Participatory Video with Most Significant Change (PVMSC) have shown that it can create an invaluable space for organisations to learn through a cycle of reflection and reshaping of programmes in line with participants’ values. This is why, in 2016, the International Year of Evaluation, InsightShare launches the PVMSC toolkit to help spread the method.

The PVMSC guide (accessible via the link provided below) presents a synthesis of the Participatory Video (PV) and Most Significant Change (MSC) techniques, focussing on the practical application of the tool. The toolkit aims to be lightweight and useable. We provide references to articles and publications where we have discussed the theory and practice of using PV for monitoring and evaluation in more detail as well as the practical application of the tool. The use of Most Significant Change (MSC) as a technique for evaluation is also carefully and thoroughly explored by Rick Davies and Jess Dart. It is recommended that anyone wanting to practice PVMSC should read and learn from this excellent manual.

→You can download the guide for free. All you need to do is follow this link, add your email address and its all yours!

Participatory Video and Most Significant Change

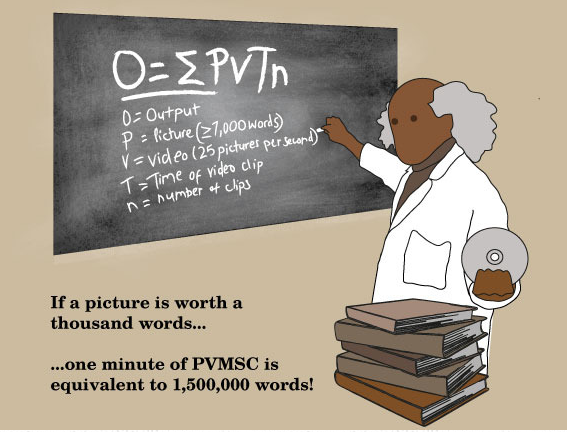

Participatory Video (PV)is a set of techniques to involve a group or community in shaping and creating their own film. The idea behind this is that making a video is easy and accessible, and is a great way of bringing people together to explore issues, voice concerns or simply to be creative and tell stories.

This process can be very empowering, enabling a group or community to take action to solve their own problems and also to communicate their needs and ideas to decision-makers and/or other groups and communities. As such, PV can be a highly effective tool to engage and mobilise marginalised people and to help them implement their own forms of sustainable development based on local needs.

Most Significant Change involves the collection and systematic, participatory interpretation of stories of significant change. Unlike conventional approaches to monitoring, MSC does not employ quantitative indicators, but is a qualitative approach.

Why PVMSC?

- Video has great potential to enhance indigenous means of communication – which, like video, are primarily visual and verbal. Ultimately it can help to link the MSC stories more closely to the localities and to the communities they come from, as well as strengthen the communities’ sense of ownership and control over the documentation and diffusion of the MSC stories.

- Pens and notepads can create barriers. With minimal training anyone can learn how to use a video camera, allowing people to tell their MSC stories in a familiar context. The process itself is fun and direct, and the results can be played back and reviewed immediately. This also helps to avoid situations where project staff end up having to speak on behalf of communities, using media that are often incomprehensible to the people themselves.

- The local screening of MSC stories encourages broader participation and could speed up the process of story collection as more people choose to get involved and contribute their own stories.

- Communities can be asked to vote on the stories, enabling us to move towards quantifying local consensus, and provide more valuable local evaluation. This process, and the reasons for selecting certain stories as most significant could also be filmed, and the footage added to the end of the individual stories.

- PVMSC can contribute to local empowerment, as the people can see where their films/stories have travelled, and the impacts they have had at the different levels, as well as providing the community with accessible and engaging video feedback and a glimpse into the world of decision makers.

- As with stories, video helps to connect people to the reality on the ground. There is a human connection that comes from seeing someone speak, even if it is on video. If you can’t bring the decision makers to the field, then we can try our best to bring the field to the decision makers!

- The fact that MSC stories can be watched rather than readwill also appeal to those project managers, administrators and decision makers who feel overburdened by paperwork. When the films are shown outside the community itself, subtitles or audio translations can be added, making the MSC video stories accessible to much wider audiences – local, regional and even global.

Lessons Learnt from case studies using PVMSC

During Insight’s experiments combing the MSC technique and participatory video, many lessons have been learned:

- MSC and participatory video can be integrated in very exciting and dynamic ways, which need to be developed further in the future.

- MSC stories can be documented by the project communities themselves, requiring little training and skill.

- Participatory video tools can be used effectively to generate video feedback from higher up the decision-making chain.

- Recording MSC stories on video means that the process of sorting and ranking them is much faster and simpler, and the accessibility of video as a medium means that the process can be opened up to far more people.

- The storyboard method developed by Insight, means that even without editing, good short MSC films can be easily produced and reviewed by key stakeholders.

Participatory video could be used to great effect in the MSC evaluation process, with the following advantages:

- It encourages broad participation in the evaluation process.

- MSC stories can be easily shared, opening up new possibilities for wider communication/dissemination.

- Video can be used and understood by anyone, including the illiterate.

- It helps strengthen the participants’ control over their stories.

- It has great potential for building broad consensus within a community.

Further reading

Nick and Chris Lunch (2006) Insights into Participatory Video: A Handbook for the Field. Insight.

C. Lunch, Combining Participatory Video with the ‘Most Significant Change’ Approach. Case study of an evaluation carried out at a workshop hosted by the Institute of Development Studies, UK, November 2005.

C. Lunch (2006) Participatory video as a documentation tool, LEISA Magazine, 22(1): 31.

C. Lunch (2004) Participatory Video: Rural People Document their Knowledge and Innovations, IK Notes 71, World Bank.

R. Davies and J. Dart (2005) The ‘Most Significant Change’ (MSC) Technique: A Guide to Its Use, MandE.

G. Ferreira, Pelican Case study: Participatory Video in the Policy Making Process: The Keewaytinook-Okimakanak Case Study, University of Guelph, Canada.

Further information

This toolkit has been produced with support from UNICEF in partnership with C4D Network.

“Participatory Video and the Most Significant Change. A Guide for Facilitators” by Asadullah, S. and Muniz, S. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Sections of the text provided above were taken from the article “Participatory video for monitoring and evaluation” at Capacity.org.

Related resources

- Download the PVMSC guide for free (you will need to provide an email address)

- To find out more about InsightShare and how we use PVMSC check out our YouTube Channel dedicated to this method

- Read more about Participatory Video for Monitoring and Evaluation and experiences with MSC

- Read more about Participatory Video

- View/download the field handbook "Insights into Participatory Video" by Nick and Chris Lunch

- Go to the InsightShare website (many more resources available!)

(0) Comments

There is no content