From Watershed Development to Ecosystem-based Adaptation: A journey to systemic resilience

Introduction

In recent decades, India has suffered great economic losses and human fatalities due to extreme weather events, such as droughts, storms or flooding. Millions of people are regularly displaced due to extreme weather. Many Indians acutely understand the urgency of adapting to climate change, particularly in agriculture, as at least half of the country’s population depends on this sector for its livelihood.

Kishan Kashinath Kondar (see main picture) is an Indian farmer who has managed to minimise the detrimental impacts of extreme weather by practising organic farming that preserves the ecosystem. That has involved using indigenous seeds and organic pesticides and fertilisers to cultivate more than a dozen varieties of crops across three seasons. Moreover, he has planted a wide range of fruit trees, and also rears livestock. This diversification and reliance on resilient crops have allowed him to consolidate his income and adapt to a changing climate. Kishan has taken part in watershed development and climate change adaptation programmes implemented by the Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR), since the mid-1990s.

This report is an assessment of the outcomes of two ecosystem-based adaptation projects from these programmes in Purushwadi and Bhojdari villages. The report shows how EbA can help build systemic resilience in ecosystems and communities.*Download the full publication from the right hand column. The key messages from the publication are provided below. See the full text for much more

Methodology

Watershed development projects were investigated to assess their effectiveness from an EbA perspective, in Bhojdari and Purushwadi villages, Ahmednagar district, Maharashtra:

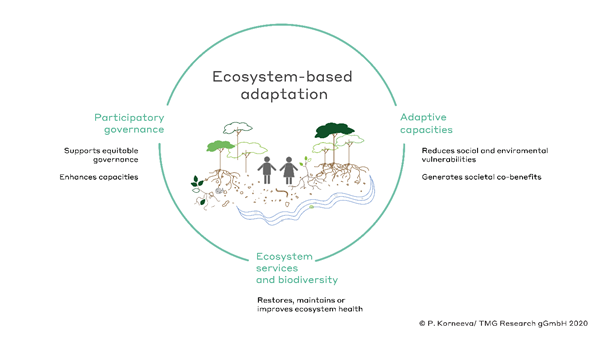

Following the definition of EbA by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which is “…the use of biodiversity and ecosystem services as part of an overall adaptation strategy to help people adapt to the adverse effects of climate change”, the study assessed the effectiveness of the watershed development interventions from an EbA lens in terms of three core Elements: the adaptive capacities of communities, ecosystem services and biodiversity, and participatory governance. Data was collected through a mixed method approach, using quantitative and qualitative methods, between November 2019 and August 2020. Quantitative data provided information on the Background context and on the Situation before and after the project implementation. Secondary data was sourced from existing project documentation or land-use analyses based on satellite images. Qualitative data helped to link the observed changes to the intervention, as well as to fill gaps in the quantitative data.

Positive outcomes were found for all three elements and the benefits for villagers were truly multi-dimensional. Farmers’ adaptive capacity improved thanks to more sustainable agricultural methods based on multi-layered farming with a mix of crop varieties, and the System of Crop Intensification. This is an agricultural practice which involves four successive steps: soil preparation and management, ample and regular crop spacing, application of locally prepared organic inputs, and micro-nutrient foliar spraying.

Results

The reintroduction of indigenous crops played a crucial role during the drought of 2018, when indigenous pearl millet was the only rain-fed crop that thrived. Moreover, the diversification of economic activity with ecotourism helped to boost farmers’ incomes. Food security and nutrition also improved, both from the switch to indigenous crops like Varai and the widespread adoption of kitchen gardens.

Alongside its economic and nutritional benefits, EbA strengthened participatory governance in both villages. Village committees were created to manage soil and water conservation infrastructure. A People’s Biodiversity Register was set up to record local knowledge of biological resources and pass this on to the younger generation. WOTR also promoted community management of water resources through the Water Stewardship Initiative and helped the villages strengthen their collaboration with government departments.

Local ecosystems and biodiversity have measurably improved. There is now greater agro-biodiversity thanks to the reintroduction of indigenous crops and the rearing of backyard indigenous poultry. Finally, large-scale soil and water conservation efforts have increased vegetation on degraded lands and boosted agricultural production due to better soil quality and moisture retention.

These results demonstrate the potential of EbA to help Maharashtra implement its action plans on climate change, biodiversity, and land degradation. A roadmap is currently being drafted through a multi-stakeholder consultation process to scale-up the adoption of EbA in Maharashtra.

Key messages for scaling up ecosystem-based adaptation

Key messages for scaling up EbA in Maharashtra

- EbA strengthens community resilience while preserving ecosystems.

- EbA increases the resilience of agricultural systems to climate change while strengthening food and nutrition security.

- EbA must be economically viable; it is therefore imperative to strengthen the income of rural communities and ensure ecosystem-based livelihoods.

- EbA can deliver cultural and health benefits since well-being depends on healthy ecosystems.

- EbA builds stronger communities, fosters local democratic processes, and pools different types of knowledge.

- EbA requires strong collaboration between communities, civil society, the private sector, government and funding agencies.

Next step

Globally, the COVID-19 crisis has shown that human encroachment into fragile ecosystems can cause the emergence of zoonotic diseases. In India, moreover, the crisis has caused massive remigration from urban to rural areas. In these two respects, the pandemic has shown that we need to manage ecosystems wisely and strengthen rural livelihoods, as was achieved in the case study villages for farmers like Kishan. Meanwhile, the climate crisis has not gone away. The roadmap to upscale EbA will offer a practical opportunity to build back better — for more sustainable and resilient communities and ecosystems.

This report was drafted by TMG Research with the collaboration of the Watershed Organisation Trust and the support of the German Environment Ministry. The report was originally published at Medium.com/enabling-sustainability. It was prepared as part of the project on “Climate-SDG Integration Project — Supporting the implementation of the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda through Ecosystem-based Adaptation”. This projectis part of theInternational Climate Initiative and financed by the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU).

For more information about similar work on Ecosystem-based Adaptation, visit the project websites: www.tmg-thinktank.com/eba and https://wotr.org/eba/

Suggested citation

Devaraj de Condappa, TMG Research (2021)From Watershed Development to Ecosystem-based Adaptation: A journey to systemic resilience.

Further readings

Related resources

- From Watershed Development to Ecosystem-based Adaptation: A journey to systemic resilience

- Publications of the Climate-SDG integration project

- Integrating ecosystem-based adaptation and integrated water resources management for climate-resilient water management

- Tools for Ecosystem-based Adaption: A new navigator for planning and decision-making

- Sourcebook: Valuing the Benefits, Costs and Impacts of Ecosystem-based Adaptation Measures

- Ecosystem based Adaptation: An integrated response to climate change in the Indian Himalayan Region

- Four Thematic Learning Briefs of the International EbA Community of Practice

(0) Comments

There is no content