Valuing Ecosystem Services in the Lower Mekong Basin

Introduction

Around 70 million people living in the Lower Mekong rely on ecosystem services provided by the Mekong River for their livelihoods and food security. However, impacts from climate change (e.g. dynamic rainfall patterns, higher temperatures, etc.), in addition to deforestation, coastal erosion, urbanization and infrastructure construction, are altering these ecosystems, threatening key crops production, livelihoods and animal habitats in the region.

Although biodiversity and ecosystem services are central to local livelihoods in the Mekong River Basin, and are therefore essential for achieving sustainable climate change adaptation in the region, the critical services that ecosystems deliver are often overlooked in decision-making regarding development projects. It is vital for policymakers to fully understand trade-offs and the long term impact of lost or diminished ecosystems on local communities.

Developed by World Resource Institute‘s Senior Economist Dr. John Talberth, these country specific guidelines for ecosystem services valuation (ESV) in each of the USAID Mekong Adaptation and Resilience to Climate Change project (USAID Mekong ARCC)’s four target countries in the Lower Mekong —Cambodia, Lao PDR, Thailand and Vietnam— include detailed explanations of ecosystem services, valuation methods and best practices, as well as policy recommendations for the decision makers of the Lower Mekong Basin countries.

Each report begins with an explanation of ecosystem services are and how they can be categorized and valuated. Each report then highlights several policy venues in the respective country where ecosystem service valuation can play a role. Next, the reports outline a seven-step process for ecosystem service valuation. Best practices are drawn from internationally recognized guidelines, such as those summarized by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) (Emerton 2013). Finally, each report offers some concluding remarks and recommendations, underscoring the importance of ecosystem service valuation in making the transition to a green economy.

The individual country reports, which contain details specific to each country, are available to download under “Further resources”. The text below is abridged and relavant to all four reports.

Ecosystem Services Typology

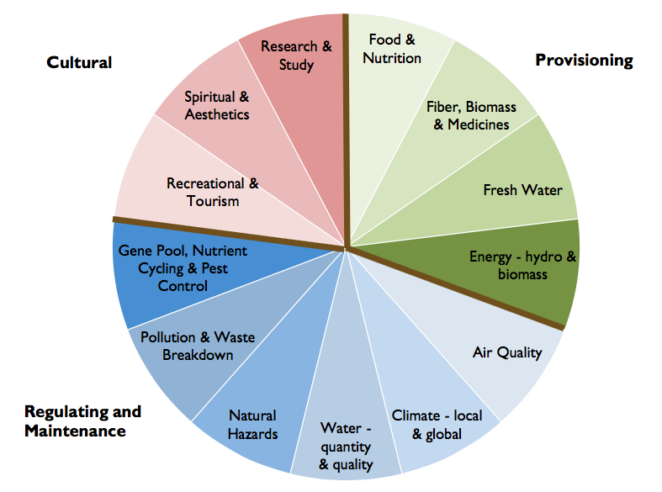

While the concept is still evolving, one of the leading efforts to synthesize existing research and develop standard classifications schemes is the European Environmental Agency’s (EEA) Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES). The CICES classification system groups ecosystem services into three categories:

- Provisioning services – Defined as all nutritional, material, and energetic outputs from living systems. They are tangible things that can be exchanged or traded, as well as consumed or used directly by people in manufacturing. Foods and medicines are some of the most ubiquitous.

- Regulating and maintenance services – Includes all the ways in which living organisms can mediate or moderate the ambient environment that affects human performance. It includes such services as the breakdown of wastes and toxic substances, flood control, maintenance of biological diversity, carbon sequestration and purification of wastewater.

- Cultural services – Includes all the non-material, and normally non-consumptive, outputs of ecosystems that affect physical and mental states of people. They include recreation, scenic and spiritual uses of the land and waters as well as the existence and bequest values people assign to places and species even from afar. The tourism industry is one of the prime beneficiaries of such services, and is increasingly being called on to pay its fair share of the costs of protecting lands and waters it showcases.

Within these major categories (called “Sections”), the CICES system further refines them into additional subcategories, as shown in Figure 1 below. The increasingly granular classification system, while complex, is designed to provide a uniform, standardized and comprehensive system for the valuation of ecosystem services.

Ecosystem Service Valuation Methods

Over the past three decades economists have developed a wide range of methods for assigning monetary values to ecosystem services. The choice of method depends upon the general type of ecosystem service (provisioning, regulating, cultural), whether the service provides direct or indirect benefits to beneficiaries, and whether the economic value is associated with use of the ecosystem or associated with its non-use values.

Direct use benefits of ecosystem services are those that involve some kind of physical interaction, such as the extraction of fish or fresh drinking water from a river or most forms of recreation. Indirect use benefits are those that do not necessarily involve physical interaction but nonetheless represent a beneficial use; for example, flood control benefits of wetlands that protect certain properties downstream even though the property owners who may benefit may not actually visit the wetlands providing this service.

Non-use values (also referred to as ‘passive use values’) on the other hand, are intrinsic values people may hold for preservation of a resource even though they may not receive any direct or indirect benefits from it (Kaval 2010; Boardman et al. 2001), but they are willing to pay for such protection. Non-use values include those associated with protecting biodiversity or natural landmarks for their own sake (existence values), preserving indigenous cultures (cultural heritage values) or the desire to pass on resources for future generations (bequest values).

The Ecosystem Valuation Estimator

Working with the Mekong Region Futures Institute, USAID Mekong ARCC developed a simple Ecosystem Value Estimationtool for non-economists, which estimates economic values of ecosystem services in order to give decision-makers a fuller picture of the economic costs of environmental conservation and degradation.

This Ecosystem Value Estimation tool calculates value ranges for ecosystems and their services based on 508 assessments conducted in the Lower Mekong Basin. Further details are described in this technical document.

Best Practice Guidelines for Conducting Ecosystem Service Valuation

Now that the potential for ecosystem service valuation has been recognized, there is a rapidly proliferating body of literature that provides guidance on the processes and best practices for valuing ecosystem services. WWF published a useful compendium of 49 separate best practice guidelines for valuing ecosystem services in general as well as particular services associated with biodiversity, forests, marine and coastal ecosystems, protected areas and wetlands (Emerton 2013). The compendium also provides links to analytical tools and data sources, and was designed to help guide valuation research in the LMB.

As the valuation guideline literature is relatively new, the processes outlined vary considerably from source to source. Nonetheless, there are several key steps that are common:

- Choose the appropriate valuation objective

- Select boundaries for the analysis area

- Identify important ecosystem types, services and values for measurement

- Incorporate existing high quality information through benefits transfer

- Conduct original valuation studies were gaps exist

- Quantify the annual benefits over time and report present values

- Sensitivity analysis

Each step is covered comprehensively in all of the country-specific guideline reports.

Conclusions and Recommendations

These reports provide guidance on standard typologies for classifying ecosystem services, methods for valuation, policy venues where valuation can play an important role, and a generalized seven-step process for best practice. As decision makers in each country consider use of ecosystem service valuation studies in the years ahead, there are three key points to keep in mind:

-

The importance of ecosystem services cannot be overemphasized. It has been reported that roughly 80 percent of the Greater Mekong’s 300 million people depend directly on the goods and services its ecosystems provide (WWF 2013). Therefore, if decision makers want good information about economic wellbeing in the LMB, they must employ the tools of ecosystem service valuation.

-

There are many policies and investments that have the potential to affect the quantity and quality of ecosystem service provision. Each report reviews several examples, but in reality, any policy and/or investment that affects the extent or functioning of intact native ecosystems will also affect the services they provide. In considering the benefits and costs of such policies and investments, impacts on the flow of ecosystem services must be considered for the analysis to be credible.

-

While the field of ecosystem service valuation is relatively new, it has now matured to the point where there is a wealth of detailed technical guidance manuals from which to draw on as well as a rich portfolio of ecosystem service valuation studies in the region that can be helpful. Many of them are cited or reviewed in these reports. Thus, when the need for valuation arises, lack of information about conducting valuation studies should not be a significant barrier.

As each country further embraces a greener pathway for economic growth, ecosystem service valuation can play a role in ensuring that the flow of goods and services that nature provides will be protected, restored and managed to enhance livelihoods, especially for those in under-resourced and marginalized communities.

(0) Comments

There is no content