Lessons Learned from the Peace Centers for Climate and Social Resilience: An Assessment in Borana Zone, Oromia National Regional State, Ethiopia

Introduction

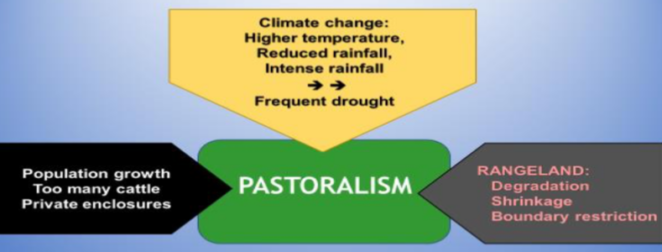

In recent decades, southern Ethiopia and other arid and semi-arid rangelands in the Horn of Africa have experienced the effects of two related threats: 1) increasingly frequent and severe droughts amplified by climate change, and 2) outbreaks of conflict among pastoralist groups whose access to natural resources has been squeezed by population growth, land development, administrative boundaries, rangeland degradation, and erratic and extreme weather.

Collaborative community activities to strengthen climate resilience, and which are focused on building key institutional relationships, may contribute to conflict prevention, and lower levels of conflict can provide the opportunity to enhance the scope and quality of climate adaptation.

Since 2014, the Peace Centers for Climate and Social Resilience (PCCSR) project, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and implemented by the College of Law of Haramaya University, has undertaken collaborative activities in pastoral communities in three districts (woredas) in Borana Zone to address community vulnerabilities to climate change and improve communities’ capacity for conflict prevention, mitigation and resolution (PMR).

This report* analyzes the climate and conflict dynamics of the project areas, how the PCCSR project activities addressed them, the results of PCCSR activities and their effects on conflict and climate resilience, and the lessons from the PCCSR pilot project’s implementation.

*Download available from the right-hand column. The text below covers key areas and findings of the report, based on the Executive Summary. Please see the full report for much more detail.

The peace centers of the PCCSR

The peace centers of the PCCSR were designed with three main objectives: 1) improving conflict resilience through collaborative community actions on climate vulnerabilities; 2) enhancing community adaptive capacity to address climate and natural resource challenges; and 3) strengthening the overall capacity of communities in conflict PMR. An important cross-cutting aim was the improvement of communications and linkages between customary and formal institutions.

Their activities were agreed upon by PCCSR project stakeholders following consultations with elders, traditional leaders, women and youth from each of the respective ethnic groups as well as government officials. These activities included (for example): the establishment of women’s peace networks; initiation of intergroup community dialogues; trainings/workshops on peace and conflict, and climate impacts and adaptation; and development of community by-laws with local government on the joint management of rangeland resources.

For more information on the peace centres see Chapter 5, from page 23 of the full text.

Methods

The assessment is based on the concepts and research methodologies used in the USAID Conflict Assessment Framework (CAF). The CAF uses key analytic categories that provide a structured way to think about conflict dynamics. These include identities, societal patterns, grievances, institutional performance, key actors, and trends and triggers of conflict.

From mid-May 2017 to early June 2017, a three-person assessment team met in Addis Ababa with USAID/Ethiopia mission staff, nongovernmental experts, officials from ministries of the federal government of Ethiopia and the Oromia National Regional State government, followed by extensive field interviews and focus group discussions in Borana.

Key Findings

Some of the lessons learnt (summarized from the Executive Summary in the full text) are provided below. See the full text for much more detail.

- Climate change — especially the stepped-up frequency of droughts — appears to be overwhelming some communities in Borana Zone.

- Annual rainfall in Borana Zone has been consistently reduced, accompanied by an increased frequency of intense rainfall events that result in loss of soil nutrients and reduced moisture absorption, inhibiting the regrowth of ground cover.

- This population is seeing an increasing stream of pastoralist “dropouts”, especially young men and women. There are concerns about the viability of pastoralism as a reliable livelihood, and many focus group participants (men and women) made it clear that they would leave pastoralism if given a viable alternative path forward.

- The success rate of pastoralist dropouts in finding a stable alternative livelihood is very low. The rising curve of pastoralist dropouts appears to be outstripping the absorptive capacity of labor markets in Borana and elsewhere in Ethiopia.

- Most pastoralists lack fundamental educational skills. There is a strong need for collective basic education, attitudinal changes and skills development for empowerment.

- Conflict is a cause — and possible consequence — of the phenomenon of pastoralist dropouts, who constitute a growing population of unemployed or under-employed internally displaced persons.

- With shrinking rangelands, two distinct land use paradigms for pastoralists are under discussion. Clear arguments for and against exist for each paradigm, and pastrolist leaders and government prefer opposing paradigms. After negotiations, however, regional government officials decided to undertake pilot certification of three dheeda areas, based on the customary territorial and ecological unit used by pastoralists in Borana.

Pressing issues and value of the PCCSR appraoch

- A rural-to-urban, unmoored and growing population of mainly young men and women without productive activities to occupy them is an urgent problem that raises serious concerns about instability and conflict.

- Going forward, the question is how institutional differences regarding land use models for pastoralists are to be managed and resolved. The PCCSR project offers a successful model that could help to fill this gap and facilitate the necessary dialogue and collaboration at the local level.

- Efforts to date to address the urgent challenge of pastrolist dropouts appear to be far from adequate. From the perspective of conflict analysis, there is a high risk that the current trajectory of incremental actions to address the issue of pastoralist dropouts will lead to an explosive and destabilizing situation in the future.

- A second challenge is establishing clearer and more firmly agreed upon systems of pastoralist land use tenure. The divergent priorities of small and tightly administered political units on the one hand and large landscapes for livelihood needs on the other reflect the basic tensions between state and society in pastoralist areas of Ethiopia.

- Religion, government and other cultural influences are penetrating more deeply into community life in Borana. Given the role of traditional institutions in conflict prevention, these changes have implications for their effectiveness. By providing organizational structures for women’s and youth groups, the PCCSR model can provide a channel for their input and contributions to managing the challenges of this changing context.

Outcomes and Impacts

- The PCCSR project areas have experienced very few episodes of conflict, and when tensions or conflict arise, violations or crimes are reported almost immediately.

- The most fundamental achievement of the PCCSR, however, is the attitudinal change identified by all project stakeholders. This is the shift from “ethnic attribution” of criminal acts and negative characteristics (aggressive, wild, violent, untrustworthy, immoral) to ascribing them to the individualswho commit acts of violence or exhibit those characteristics.

Enabling Factors

The process needed to produce these results, while not requiring large expenditures, involves systematic, sequential, structured and iterative activities to build knowledge, social capital and trust. These activities need sufficient time to be fully implemented and to take hold. The effective functioning of the peace committees and women’s and youth groups is enhanced by a constructive collaborative relationship between local government and customary institutions.

Climate change has been an effective organizing principle and center of gravity for the PCCSR project for the compelling reason that it is an “external threat” experienced by all ethnic groups and clans in Borana. The critical need to respond to climate threats provided a meaningful rationale and strong incentive for interethnic dialogue and collaboration. Community discussions about climate challenges usefully broadened and strengthened the agenda for interethnic and interclan dialogue about conflict issues.

Climate change adaptation measures that directly or indirectly reduced competition for grazing areas and water points reduced the potential for conflict. While climate change adaptation activities to harvest water and reduce erosion were important for the direct benefits they provided for livelihoods, the rehabilitation and sharing of water ponds was a more powerful and important contribution to conflict prevention.

This publication was prepared for the United States Agency for International Development Adaptation, Thought Leadership and Assessments (ATLAS) project by Chemonics International Inc.

Suggested Citation

USAID (2017) Lessons Learned from the Peace Centers for Climate and Social Resilience: An Assessment in Borana Zone, Oromia National Regional State, Ethiopia. USAID: Washington D.C., USA

PCCSR builds upon the hypothesis proposed in Mercy Corps’ 2012 report, “From Conflict to Coping”, that conflict PMR is a key piece of climate adaptation, as peacebuilding efforts may contribute to conditions that foster greater freedom of movement and enable better access to natural resources (such as pasture and water) that allow pastoralists to deploy strategies to cope with climate shocks.

(0) Comments

There is no content