Strengthening External Emergency Assistance for Managing Extreme Events, Systemic, and Transboundary Risks in Asia

Introduction

Climate change can exacerbate extreme weather events, putting severe stress on the disaster risk management capacity of affected countries (IPCC, 2012). Such countries may require more external emergency assistance (EEA), especially those with seriously impaired capacity to manage disasters. This can then put an additional burden on the national budgets of EEA donor countries.

As a result, there is an emergent view that the EEA has costs and benefits for both the donor and recipient countries, and that such assistance can have climate security implications. However, there has been not much research on identifying specific climate security implications of increased EEA needs, and how best the EEA can be managed in such a way that both the donor and recipient countries can maximize their climate security. This necessitates a revisit of the EEA in terms of climate security. Viewing the issues associated with extreme events and EEA through the lens of climate security can help us to move away from a short-term thinking paradigm towards long-term thinking, with an emphasis on risk communication and risk mitigation.

EEA has significant implications for both the recipient and donor countries. EEA, if not designed well, may cause recipient countries to become dependent on such assistance. Conversely, EEA is an economic cost to the donor countries, and it is a lost economic opportunity that the donor country could have invested elsewhere with better outcomes for its people. Hence, improving the EEA is beneficial to both donor and recipient countries.

Keeping the above background in view, this paper explores the possibilities for enhancing the effectiveness of EEA received by countries affected by extreme weather events. Towards this objective, the paper explores the linkage between the climate fragility of a country and the development status of that country, by developing a Climate Fragility Risk Index (CFRI). Further, the paper presents a critical threshold idea for the delivery of EEA to the countries affected by extreme weather events. Based on a set of stakeholder workshops organized in the Philippines and Pakistan, the paper goes on to present various means for strengthening the long-term risk reduction by learning from the EEA experiences of recipient and donor countries.

This weADAPT article is an abridged version of the original text, which can be downloaded from the right-hand column. Please access the original text for more detail, research purposes, full references, or to quote text.

Current Status of External Emergency Assistance

Every year, millions of dollars are being spent on EEA. Between 2000 and 2019, Asian countries received emergency assistance to the tune of USD 100 billion (UN-OCHA, 2021). In addition to financial resources, countries are also employing their military to deliver disaster relief related services. A survey conducted by the American Security Project (2012) indicates that militaries in more than 70% of countries around the world have humanitarian assistance and relief as a critical mission. The role of the military in disaster assistance may increase in the future, putting such personnel in high demand and possibly escalating the cost of humanitarian assistance due to military deployment.

However, extreme events, such as those with a return period of 50 or 100 years or more, are still a challenge for governments especially when they take place at a place and time that is least expected. This is largely due to a lack of experience and expertise in dealing with extreme events, and a lack of capacity, especially at the local level. As a result, many governments require external support for rescue and relief in the short term and for reconstruction and rehabilitation in the long term.

Transboundary risks on Japan will increase in the future

Climate change projections indicate that losses associated with cyclones will increase, there is likely to be an increase in the average maximum wind speed of cyclones, and flood losses in many locations will increase in the future (high agreement) (IPCC, 2012). This indicates the possibility that developed countries like Japan may have to allocate more resources to the EEA if the capacity of vulnerable countries is not significantly improved in the future. This could have climate security implications for both donor and recipient countries.

As such, Japan’s climate security is affected by a set of complex factors. For example, one of the major sources of climate threat to Japan is related to its food imports. Japan imports more freshwater than the water withdrawn within its borders and saves nearly 20 km3 of water by importing food. Climate change impacts on exporting countries will result in food and water insecurity for Japan (Inuzuka et al., 2008).

Disasters elsewhere can have a significant impact on Japan’s economy. For example, the Bangkok floods of 2011 caused a total estimated loss of USD 47 billion, with 90% of the losses accrued by Japanese companies and related investments (Prabhakar & Shaw, 2020). This indicates how the impacts of extreme weather events are increasingly becoming transboundary.

Methods and Tools

Development of Climate Fragility Risk Index (CFRI)

In this paper, Climate Fragility Risk Index (CFRI) was developed as a means of quantifying the climate fragility of countries. CFRI is a unit-less index, developed using indicators that directly affect the fragility of states and institutions. The index shows the relative climate fragility of countries. The purpose of CFRI is also to see if state fragility has any impact on the state’s ability to provide effective relief assistance to affected people.

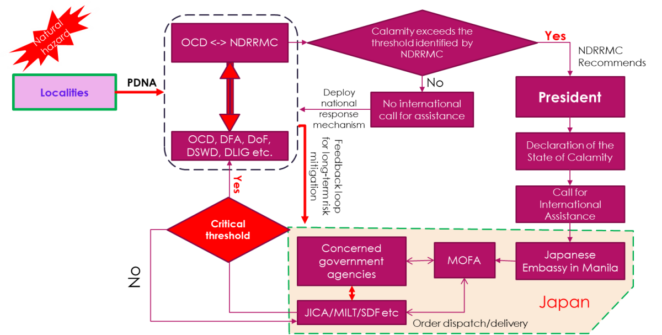

Developing critical threshold levels for receiving external emergency assistance

This is a new idea that has been developed by the authors of this paper with no known precedence in the existing literature. The basic assumption of the critical threshold levels for EEA is that countries tend to need EEA when disaster damages cross certain critical levels of damages, including loss of life and economic damage, exceeding the needed capacity to manage the emergency. Disaster damage tends to vary even within a country due to varying levels of intensity of disasters, location of the disaster (e.g. highly developed urban areas vs poorly developed rural areas with different disaster management and mitigation capacities), and the timing of the disaster (e.g. more recent disasters of the same magnitude may cause less damage as governments are continually improving the disaster risk mitigation efforts). Hence, making sense of this complexity is crucial to understand under what circumstances a country may need EEA so that the assistance providers can be vigilant and provide appropriate assistance (amount and nature) quickly.

Results and discussion

The Climate Fragility Risk Index (CFRI) investigation revealed that the amount and form of climate fragility risks vary by country (Figure 1). This emphasizes the importance of developing country-specific strategies for addressing climate fragility risks. It also emphasizes that the ability of countries to respond to climate extremes can vary due to different underlying fragility risks. The average CFRI for developing countries, which include Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Pakistan, and the Philippines was 0.76. For developed countries, comprising Australia, Japan, and the Republic of Korea, the CFRI was 0.66, showing a marginally lower CFRI than developing countries.

Figure 1. Climate Fragility Risk Index (CFRI) of countries in Asia and Oceania

Variances in exposure to sea-level rise (where Vietnam and Thailand are particularly susceptible) and food price volatility accounted for the majority of the differences between countries (where Pakistan scored highest). When it came to metrics of internal displacement and the regulatory quality of country governance systems, there was much less variation. Because of its high sensitivity to water stress and high food price volatility, Australia had a comparatively high CFRI among developed countries.

The critical threshold analysis indicated that countries have different critical thresholds for EEA (Table 1). The PCA analysis has helped to reduce the factors down to two principal components. After conducting the PCA analysis, a regression equation for EEA dependence was developed with two principal components.

Taking the example of the Philippines, the analysis revealed that the Philippines tends to call for EEA when Principal Component 1 reaches a value of 58522475. Here, Principal Component 1 is comprised of disaster impact indicators while Principal Component 2 consists of macroeconomic capacity. The composition of Principal Components varies by country as shown in Table 1. The percentage σ² in the table indicates the proportion of variance explained by each principal component. It can be observed that in most cases, GDP and poverty are the common factors in PC1 while the number of people affected or dead are the most common factors in PC2. This indicates that the country’s economic capacity is the most important factor in determining whether or not a country calls for EEA.

Table 1. Principal components of the critical thresholds for selected countries in Asia

|

Country |

Principal Component 1 |

% σ² |

Principal Component 2 |

% σ² |

|

Afghanistan |

GDP, poverty, affected |

42 |

Dead, governance |

29 |

|

Bangladesh |

Poverty, GDP, governance |

50 |

Affected, dead |

23 |

|

China |

Damage, dead, governance |

47 |

Poverty, GDP, affected |

26 |

|

India |

Poverty, GDP, affected, dead |

39 |

Damage, governance |

21 |

|

Indonesia |

GDP, poverty, governance |

59 |

Affected, dead |

28 |

|

Pakistan |

Poverty, governance, GDP, affected |

58 |

Dead |

24 |

|

Philippines |

Dead, damage, affected |

63 |

Poverty, governance, GDP |

32 |

|

Sri Lanka |

GDP, poverty |

41 |

Dead, affected, governance |

26 |

|

Vietnam |

Governance, GDP, damage, poverty |

58 |

Affected, dead |

25 |

Conclusions

Climate change has significant implications for extreme events and as a result, will make many vulnerable countries depend on EEA, including in Asia. This is likely to have an impact on both recipient and donor countries. As a major donor in Asia, Japan will be profoundly impacted. To some extent, EEA has costs and benefits for both donor and recipient countries. Hence, any improvements in EEA will benefit both the donor and recipient countries to a varying degree. Future improvements to EEA should be made by keeping the climate security and fragility concepts in mind as they can guide countries to ensure positive and long-term benefits from short-term relief engagements. They can also help countries to minimize dependency on external assistance.

The critical threshold concept can deliver multiple benefits for fine-tuning EEA in the aftermath of extreme events such as typhoons, as there is often very little time for the national governments to evaluate the situation and respond adequately. To address the issue of EEA effectiveness, we have shown how the climate fragility of countries can have an impact on the development status of countries and in turn possibly influence their dependency on EEA. We have also shown the concept of a critical threshold for extreme events and argued that this concept can be employed to pre-empt EEA delivery effectively. However, the use of such tools needs to be implemented without impinging upon national sovereignty, as donor countries have the right to decide how to support the affected countries (i.e. either voluntarily or upon request) and how the EEA recipient countries want to receive assistance (e.g. the nature and amount of assistance).

Whether or not countries such as Japan, which mainly only respond to official requests for EEA by the affected countries rather than responding voluntarily, can utilize the concept of critical threshold remains to be seen. Japan may still be able use this analysis to strengthen future EEA by looking at the past experiences and find ways to strengthen its response, develop country-specific EEA strategies for maximizing effectiveness, and use future climate projections to understand EEA implications.

During the consultations organized by the authors, it became evident that countries in Asia are in favor of improving their disaster relief assistance mechanisms and are willing to engage with international stakeholders to harmonize measures for delivering focused relief assistance with a long-lasting impact. However, some questions remain which will be important to move forward. For example, it is still not clear how the relief assistance requests are treated by donor countries such as Japan, i.e. what priorities the donor considers before delivering the assistance, what determinants guide the donor to provide external assistance, how a donor consults with other agencies within the donor country, and how the final decision-making is done on what to deliver and how. Is it always the request of the recipient country that prevails, or do donors consider long-term implications in taking decisions?

There are limitations concerning the development of the critical threshold concept, including limited data availability, fragmented data i.e. data spread across different ministries and departments, and sensitivity of sharing data with foreign governments, especially in terms of the number of militaries deployed, the location of stock, timeframe for deploying certain types of relief etc. There is a need to address these issues before coming up with a reliable decision support system for strengthening EEA and eventually minimizing dependency over the medium to long term.

Acknowledgements:

The authors are grateful for the financial support received from the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (2-1801), Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (2-2102), and Strategic Research Fund (SRF) of IGES.

©Sivapuram Venkata Rama Krishna Prabhakar, Kentaro Tamura, Naoyuki Okano and Mariko Ikeda. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction of the work without further permission provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Suggested Citation:

Prabhakar, S.V.R.K., K. Tamura, N. Okano, and M. Ikeda. 2021. Strengthening External Emergency Assistance for Managing Extreme Events, Systemic, and Transboundary Risks in Asia. Politics and Governance.9(4) (2021): Climate Change and Security. DOI:https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v9i4.4457

Related Resources

Related resources

- Disaster response: The 72-hour Emergency Assessment approach

- Exploring the adaptive capacity of emergency management using agent based modelling

- Assistance to Local Communites on Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction in Bangladesh

- Targeted Topics: High-level political support & sectoral integration in NAP processes

(0) Comments

There is no content