The Uncertainty Handbook: A Practical Guide for Climate Change Communicators

Introduction

For the public, uncertainty is a significant barrier to engaging more readily with climate change. For policy-makers, the focus on uncertainty can obscure the important messages underneath. And too often, climate scientists find themselves apologising for what they don’t know, rather than confidently communicating what they do know.

Partly, this is because political players who are opposed to societal action on climate change have intentionally manufactured distrust around the science of climate change, exaggerating areas of uncertainty while down playing areas of strong consensus and agreement.

But even without such distorting influence, the communication of uncertainty is still a formidable challenge.

The Uncertainty Handbook – written by Dr Adam Corner, Prof Stephan Lewandowsky, Dr Mary Phillips and Olga Roberts and published through the Climate Outreach and Information Network (COIN) and the University of Bristol – offers some strategies for closing the gap between people’s intuitions and the scientific implications of uncertainty in the climate change debate.

Communicating Uncertainty*

*condensed excerpts from the handbook

1. Manage your audience’s expectations

Science is often presented by the media or taught in schools as a series of definite facts and figures. As a consequence, people have different expectations about uncertainty in science, relative to ‘everyday’ situations where uncertainty is seen as a given.

Emphasising that ‘science is a debate’ as opposed to ‘science is a fixed body of facts’ can influence people’s motivation to act on uncertain messages.

- Use analogies from ‘everyday life’ so people can see that uncertainties are everywhere

- Emphasise that science is an ongoing debate, and just because scientists don’t know everything about a subject, they do know something. We know that the climate is changing, and that delaying our response to this increases the risks.

2. Start with what you know, not what you don’t know

Too often communicators give the caveats before the take-home message. On many fundamental questions — such as ‘are humans causing climate change?’ and ‘will we cause unprecedented changes to our climate if we don’t reduce the amount of carbon that we burn?’— the science is effectively settled. Communicators should not shy away from stating that clearly. Uncertainty at the frontiers of science should not prevent focusing on the ‘knowns’.

If you can, trial or test your messages first to see how they are received. There is no substitute for audience research when it comes to constructing successful climate messages, and using language that resonates with the people you want to engage.

3. Be clear about the scientific consensus

Having a clear and consistent message about the scientific consensus is important because some research suggests it is a ‘gateway belief’ that affects whether people see climate change as a problem that requires an urgent societal response.

All of the world’s national science academies agree that humans are causing climate change, and that this will have serious negative impacts unless action is taken to prevent it. 97% of climate scientists and virtually all of the world’s climate science literature endorse the idea that humans are causing climate change.

Use a graphic such as a pie chart to visually enhance the message; use a ‘messenger’ who is trustworthy to communicate the consensus; and/or try and find the closest match between the values of your audience and those of the messenger.

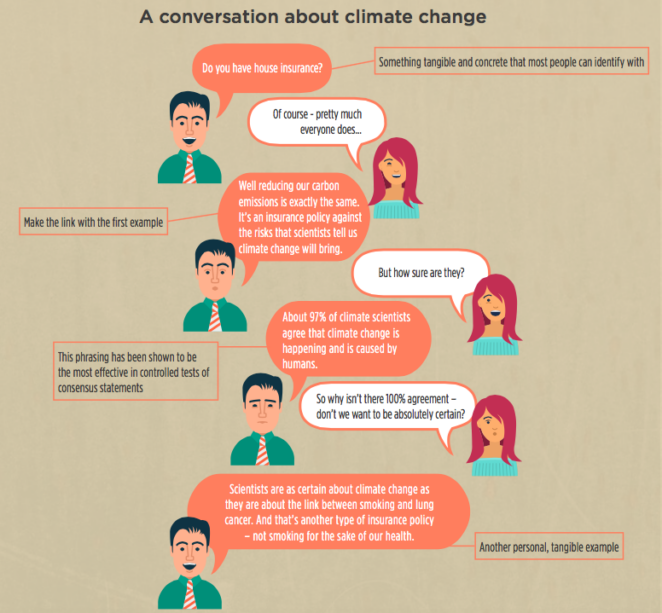

4. Shift from ‘uncertainty’ to ‘risk’

Most people are used to dealing with the idea of ‘risk’. It is the language of the insurance, health and national security sectors. So for many audiences — politicians, business leaders, or the military — talking about the risks of climate change is likely to be more effective than talking about the uncertainties.

Shifting from an ‘uncertainty’ to a ‘risk’ framing also makes it easier for people to weigh up the costs and benefits of inaction, rather than getting stuck in the perception that knowledge is still imperfect.

“If people don’t see it impacting on their daily lives it’s very difficult to communicate risk and uncertainty.”

5. Be clear what type of uncertainty you are talking about

A common strategy of people who reject the scientific consensus is to intentionally confuse and conflate different types of uncertainty.So, it’s critical to be clear what type of uncertainty you’re talking about.

For example: Cause of Climate Change

DO say “Scientists are as certain about the link between human behaviour and climate change as they are about the link between smoking and lung cancer.”

DON’T say “Although we can never be 100% certain of anything, it is highly likely that changes in our climate are due to an anthropogenic influence.”

6. Understand what is driving people’s views about climate change

When a subject is politically charged people filter the scientific facts according to their own political views. In fact, there is a consistent relationship between ‘conservative’ political views (i.e., to the right of centre) and doubt about the reality or seriousness of climate change.

Use ways of communicating about climate change that do not threaten the belief systems of the audience, or which use language that better resonates with their values. For example, for ‘conservative’ audiences risk- aversion, pragmatism, security, and a desire to ‘conserve’ natural beauty may offer a more constructive way of discussing climate change uncertainties.

7. The most important question for climate impacts is ‘when’, not ‘if’

The further into the future potential risks and hazards are the easier they are to ‘discount’ or ignore. Climate change is a notoriously ‘distant’ risk for most people — not here, and not now. And the uncertainty inherent in climate predictions opens the door to wishful thinking about how dangerous climate change really is.

Climate change predictions are usually communicated using a standard ‘uncertain outcome’ format. But flip the statement around — using an ‘uncertain time’ framing — and suddenly it is clear that the question is when not if sea levels (for example) will rise by 50cm.

8. Communicate through images and stories

While the IPCC reports are an essential means of quantifying scientific uncertainty, a series of studies have found that the people severely underestimate the meaning of some probability statements (e.g., ‘very likely’), while overestimating the probability of others. The reality is that most people understand the world through stories and images, not lists of numbers, probability statements, or technical graphs, and so finding ways of translating and interpreting the technical language found in scientific reports into something more engaging is crucial.

“The use of case studies is a good way to engage people who haven’t experienced extreme weather events directly… This really hits home with people – personal narratives.”

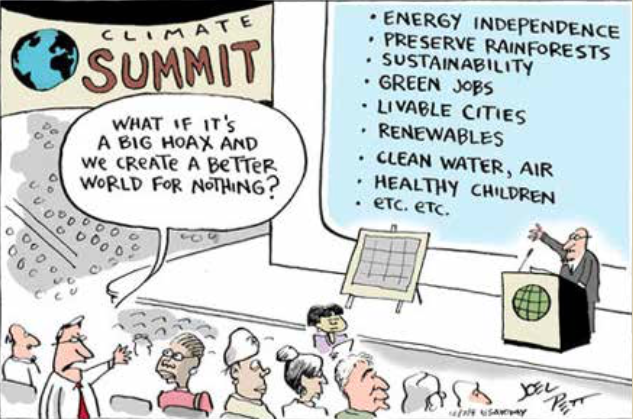

9. Highlight the ‘positives’ of uncertainty

Uncertainty is not necessarily a barrier to communication if a positive ‘framing’ of the problem is used. When uncertainty is used to indicate that losses might not happen if preventative action is taken (i.e. the positive frame), people are more likely to indicate stronger intentions to act in a sustainable way.

10. Communicate effectively about climate impacts

The tangible and traumatic experiences that arise from extreme weather events reduce the ‘psychological distance’ between people and climate change, allowing affected communities to relate more easily to the issue.

But the question ‘is this weather event caused by climate change?’ is misplaced. When someone has a weak immune system, they are more susceptible to a range of diseases, and no one asks whether each illness was ‘caused’ by a weak immune system. The same logic applies to climate change and some extreme weather events: they are made more likely, and more severe, by climate change.

Engaging people around extreme weather events must be done in a way that speaks to your audience’s values, and interests. For example:

“A volatile climate means a vulnerable tourist industry”

“Unpredictable seasons produce unreliable harvests”

11. Have a conversation, not an argument

Despite the disproportionate media attention given to ‘sceptics’, most people simply don’t talk or think about climate change all that much. This means that the very act of having a conversation about climate change — not an argument or repeating a ‘one-shot’ slogan — can be a powerful method of public engagement.

12. Tell a human story, not a scientific one

People’s tendency to prioritise daily personal experiences over statistical learning, and their existing political views, have a far greater influence on our beliefs about climate change than the error bars on scientists’ graphs. When people feel inspired by the answers to climate change, they no longer see uncertainty about the future as the central question. This means that telling human stories about the people affected by climate change (and how they are responding to it) is crucial – shifting climate change from a scientific to a social reality.

Authors & Funding

Dr Adam Corner, Research Director, COIN; Honorary Research Fellow in the School of Psychology, Cardiff University

Professor Stephan Lewandosky, School of Experimental Psychology and Cabot Institute, University of Bristol

Dr Mary Phillips, School of Economics, Finance & Management, University of Bristol

Olga Roberts, Researcher & Project Coordinator, COIN

Design: Oliver Cowan (www.olivercowan.co.uk)

The Uncertainty Handbook was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council – grant number ES/M500410/1 – and by a grant from the Research Development Fund of the Worldwide Universities Network.

Recommended Citation

Corner, A., Lewandowsky, S., Phillips, M. and Roberts, O. (2015) The Uncertainty Handbook. Bristol: University of Bristol.

Note: the full handbook is available for download to the right of the body text higher up this page (see “Featured Download”), as well as being available on the COIN website: http://www.climateoutreach.org.uk/portfolio-item/uncertainty-handbook/

(1) Comment

Note that The Guardian gives special mention to this handbook and puts emphasis on these tools for communicating climate change more effectively. See here: http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2015/jul/06/12-tools-for-communicating-climate-change-more-effectively