Urban heat in South Asia: Integrating people and place in adapting to rising temperatures

Introduction

Heat has uneven spatial and social distributions, with wide variations in temperatures and adaptive capacities across buildings, communities, and cities around the world. Urban areas often experience higher temperatures by absorbing more solar radiation than surrounding rural areas, a phenomenon called the urban heat island (UHI) effect. Existing heat risks in cities are amplified by warming temperatures from climate change. Global surface temperatures have risen 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels and are continuing to rise.

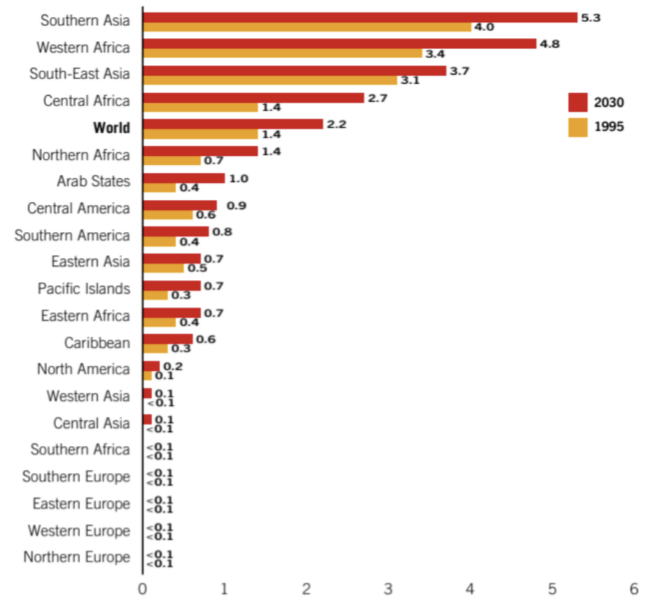

South Asia, home to a quarter of the world’s population, is a region highly vulnerable to the impacts of urban heat. Although the region is accustomed to heat, rapid urbanization and climate change are pushing the region’s limits of adaptation with lethal consequences.

This policy brief probes urban heat vulnerabilities across both people and place in South Asia to underscore the importance of integrating population- and settings-based approaches in heat planning and policymaking processes at the municipal level:

- Section 2 probes heat in South Asian cities through the different layers of the urban environment: buildings, communities, and cities. (p. 3-12)

- Section 3 then adds the human element and explores different population groups that are vulnerable to urban heat in the region: children, informal workers, and residents of informal settlements. The relevance and reasonings for the groupings are discussed at the start of each section, noting where nuances and complexities lie. (p. 13-18)

- Finally, Section 4 provides three regionally specific recommendations for how urban heat management can be improved in South Asia. (p.19-23)

This article is an abridged version of the original text, which can be downloaded from the right-hand column. Please access the original text for more detail, research purposes, full references, or to quote text

The Urban Environment

The built environment shapes spatial variability in urban heat. This section explores heat vulnerabilities and management strategies in the urban environment around three major clusters of increasing scale: buildings, communities, and cities. The influence of the built environment on heat vulnerabilities and resilience in cities is highlighted in these three clusters, which is later linked to the differential social vulnerabilities to urban heat in the next section.

Buildings:

- Buildings play a central role in influencing overall heat exposure and thermal comfort. This arises from the large time spent indoors and the corresponding impacts indoor air temperatures have on heat risks.

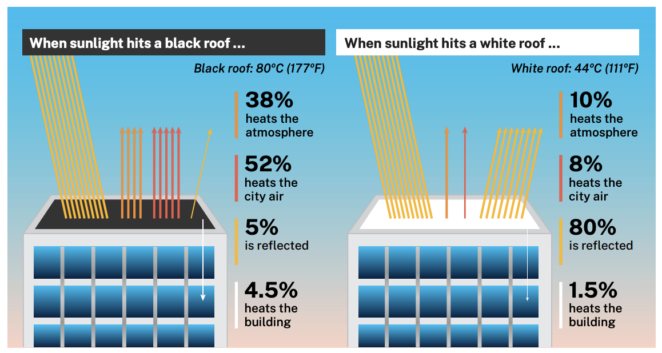

- The use of heat-trapping materials is exacerbating urban heat risks in South Asia. Rapid urbanization and population growth have resulted in many buildings being non-engineered, temporary, or self-built.

- More studies are needed to understand the indoor heat profiles in South Asia.

- In the absence of targeted public policies and programs, non-governmental organizations are helping to improve the heat resilience of buildings.

Communities:

- Intra-urban temperature differences arise between communities.

- Green and blue spaces play a key role in managing community heat risks. Green spaces can help mitigate the UHI effect through shade cover and evapotranspiration. Similarly, surface water bodies provide cooling through evaporation and the oasis effect.

- Many South Asian urban communities are ill-equipped for managing current and future heat risks. High-density living, along with low permeation of green and blue spaces, creates heat management challenges for a large number of communities in South Asia.

- Further studies on intra-urban temperature differences are needed in South Asia.

Cities:

- The impacts of extreme heat can be greatly minimized through city-level measures.

- Urban heat is a rising risk across South Asian cities that is often underestimated and underreported.

- Ahmedabad’s Heat Action Plan (HAP) has been a leading example of city-led action. Heat management plans can take many different forms but generally consist of a central framework for assessing, managing, coordinating, and responding to local heat risks.

- The number of urban heat plans is growing across South Asia but with much room for improvement.

- Advanced heat management strategies can deliver more targeted interventions with greater co-benefits.

- A core element of all effective heat management plans at the municipal level is clear responsibility and ownership.

- In addition to establishing a dedicated institutional structure, cities in South Asia can address the structural drivers of urban heat vulnerabilities in their heat management plans.

Refer to pages 3-12 of the policy brief to explore all of these points in more detail.

Vulnerable Population Groups

Urban heat vulnerabilities extend beyond the built environment to include the people within it. This section explores the relationship between people and place in urban heat in three vulnerable population groups in South Asia that are particularly relevant for the region’s economic development and poverty alleviation: children, informal workers, and residents of informal settlements.

Children:

- Children are naturally vulnerable to heat stress and these vulnerabilities are heightened in South Asia.

- Heat exposure can compromise children’s quality of life and development trajectories.

- Protecting South Asia’s youth population from heat stress is vital to unleashing the region’s human capital potential.

- Studies outside of South Asia have shown negative correlations between heat and learning.

- Local studies are needed to understand how heat is impacting learning in South Asia.

Informal workers:

- Rising temperatures are a major occupational hazard for South Asia’s informal workers. South Asia has some of the highest numbers of informal workers in the world.

- Informal workers are more likely to engage in manual or outdoor work which increases heat risks.

- Many informal workers lack the capacity to absorb heat-related work disruptions.

- Lost labor due to rising heat and humidity levels is an economic risk to South Asia.

Residents of informal settlements:

- Residents of informal settlements face heightened heat risks in South Asia.

- Spatial vulnerabilities intersect with socioeconomic vulnerabilities in informal settlements.

- Residents of informal settlements are less likely to have access to the basic services or infrastructure necessary to adapt to rising temperatures.

- Future urban heat analysis and management efforts in the region need to account for the nuances and complexities of informality to better target resources towards the more vulnerable households in riskier areas of South Asian cities.

Learn more about vulnerable population groups in pages 13-18 of the policy brief.

Recommendations

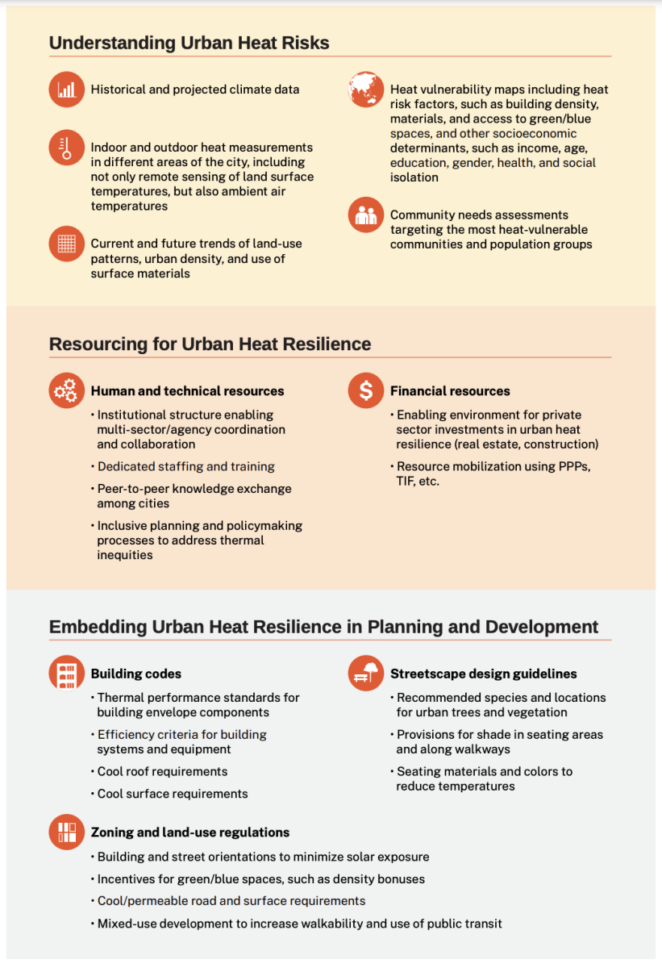

This policy brief reviews the current state of knowledge of urban heat in South Asia, outlining the gaps in theory and practice for urban heat management in the region. The analysis forms the basis of three major recommendations and a conceptual framework to provide policymakers with direction on where greater attention and resources are required to improve urban heat management in South Asia:

- Improve data collection and analysis: Further data are required to adequately identify, manage, and monitor South Asia’s urban heat risks.

- Integrate people and place in urban heat management:To date, most heat management plans and policies have taken either a settings-based or a population-based approach. Future heat management efforts should be designed to address both social and spatial vulnerabilities.

- Manage slow-onset, longer-term impacts of urban heat:Going beyond heat management plans that focus on preventing excess morbidity and mortality, cities in South Asia should develop planning and policymaking processes that aim to incorporate and address slow-onset, longer-term impacts of heat that threaten human capital accumulation, social welfare, and economic development.

Based on these recommendations, this policy brief outlines a framework (Figure 8) for South Asian planners and policymakers to enhance urban heat resilience, with practical considerations to integrate people and place in addressing the longer-term impacts of urban heat on the region’s economic development and prosperity.

Explore the recommendations in more detail on pages 19-23 of the policy brief.

Suggested Citation:

Kim, Ella Jisun, Grace Henry and Monica Jain. 2023. “Urban Heat in South Asia: Integrating People and Place in Adapting to Rising Temperatures”. Policy Brief. Washington DC. The World Bank.

Related resources

- Integrating Climate Adaptation: A Toolkit for Urban Planners and Adaptation Practitioners

- Hong Kong’s July heatwaves highlight the city’s lack of holistic climate governance

- Community Commons as Socially Just and Adaptive Spaces

- Even half a degree of warming matters for South Asia’s urban poor

- Mainstreaming adaptation to climate change within governance systems in South Asia

(0) Comments

There is no content